2022 | TOURISM AS ENVIRONMENTAL DISASTER

The Impacts Of Tourism On Cultures, Communities And Environments

Ulrike Heine | David Franco | George Schafer

Introduction

The US Atlantic Coastline, extending from Maine to Florida a distance of over 2,000 miles, is home to valuable and delicate coastal landforms such as sea islands, archipelago, peninsulas and barrier islands. These environments provide habitat for a plethora of plants and wildlife as well as services that support our well-being, such as agriculture and recreation, and serve to buffer the coastal mainland against wave damage, disastrous storm surge and flooding. Host to unique landscapes such as white beaches, rich vegetation and marshlands, Atlantic coastal landforms – often separated from the mainland, and therefore remote and protected – have historically been home to, and allowed for the preservation of unique, indigenous, vulnerable populations and cultures. As one example, during the Jim Crow era the self-sustaining Gullah-Geechee communities found a safe haven on the string of coastal barrier islands spanning from the Carolinas to North Florida. Unfortunately, Atlantic coastal cultures, communities and ecosystems are increasingly at risk from the negative impacts of both climate change and tourism. Over time, as these once-remote Atlantic coastal landforms were connected to the mainland by bridges, causeways and ferries, they have had to metabolize a massive invasion of the tourist industry, injecting new economies, infrastructure projects, higher ship traffic, travel-oriented constructions at various scales, from vacation homes to hotels of all sizes, and gated all-inclusive resorts – to disastrous effect. The short and longterm consequences have impacted both the ecosystems of these areas and the communities inhabiting them, leading to the commodification of these coastal landscapes. Understanding the notion of environment in its broadest sense and acknowledging the disastrous impact of parasitic tourist practices, this studio will address two major intertwined challenges that are threatening the existence of Atlantic coastal landforms and their specific cultures:

SOCIAL AND CULTURAL CHALLENGES. As tourist developments spread, degrading the very landscapes they are attracted to, they systematically displace low-income groups from the most natural areas of the islands to the mainland. Ironically, though not unexpectedly, indigenous, African-American and working-class communities are the first ones to be removed through unregulated real estate practices, gentrification, abuse of property rights and an inability to adapt to the overwhelming pressure of a tourism economy.

ENVIRONMENTAL CHALLENGES. Tourism creates unique pressures on places. It has a negative impact on biodiversity and often overburdens local resources (water, land, energy, pollution and waste) due to concentration in space and time (seasonality of population density). Tourism-based development – whether gleaming towers in Atlantic City or recreational vehicle parks along the Chesapeake Bay – results in alterations to the landscape often leading to harmful runoff, sand erosion, rapid sea level rises, and extreme weather events, thus causing a progressive reduction of Atlantic coastline and, in a downward spiral, reducing the protections these Atlantic coastal landforms provide for the mainland. These negative effects of tourism only serve to exacerbate and accelerate the effect of climate change on coastal environments.

THE PROJECT

The main objective of the studio is to explore strategies for the restoration and alternative occupation of 6 Atlantic coastal sites – Fire Island, NY; Atlantic City, NJ; Cherrystone, VA; Sunset Beach, NC; St. Helena Island, SC, and Key West, FL – through the design of a new, self-sustaining tourist community. We propose to look at tourism as a socially and environmentally problematic industry, for which we need to formulate alternatives that are socially responsible, environmentally respectful and economically sustainable. The proposals that emerge from this alternative position should reinvent the architectural models commonly built by the tourist industry, and explore new forms, organizations, materials, and programs. A radically new approach to what tourism should be must reflect in radically new architectural ideas that carefully respond to the complexities of the issue and the sites. Program development and design solutions for each site should emerge from/respond to: • The histories, cultures and communities traditionally occupying these coastal sites, along with the mechanisms that led to their erasure by tourism. Understanding the specificities of communities that are affected by travel industries is critical in proposing new modes of inhabitation and land-occupation that not only recognize what was lost in this process, but also contribute to the development of guidelines for future interventions. Understanding the histories and cultures of tourism – the who and why of tourism specific to each site – will also be critical to the development of innovative programmatic/ design solutions. • The climatic and geographic conditions/threats present for each site, as well as technologies, materials, and building techniques that respond and adapt to these conditions. We will explore creative and innovative alternatives to conventional approaches and technologies.

SITE STRATEGIES

As part of the studio we will work in the preparation of the 2022 AIA COTE Students’ Competition, leveraging its environmental requirements to build the case for new models/forms of coastal tourism. Successful projects will be carefully adapted to their local conditions (climate, landscape, economy, society and culture). The better adapted, the more efficient use of resources. In that sense, the tourism futures explored in the studio should transform a destructive, parasitic industry into one that achieves a level of balance and symbiosis with its surroundings.

SITES

SITE 1: Fire Island, NY.

40°39'49"N 73°04'15"W

SITE 2: Atlantic City, NJ.

39°21’44”N 74°24’46”W

SITE 3: Cherrystone, VA.

37°17’12”N 76°00’51”W

SITE 4: Sunset Beach, NC.

33°52’56”N 78°30’43”W

SITE 5: St. Helena Island, SC.

32°23’11”N 80°34’36”W

SITE 6: Key West, FL.

24°32’54”N 81°48’07”W

RESTORING A HAVEN

WILLIAM SCOTT | CONNOR SMITH

Starting in the mid-20th century, artists and creatives in the New York City queer community adopted Fire Island Pines as a haven and destination. The affordability and opportunity to create their own community underpinned an environment that cultivated free expression. But over the years, like many other creative enclaves in New York and elsewhere, higher income brackets have infiltrated in search of valuable property and cachet. This has priced out creatives and ultimately jeopardized The Pines’ identity and sense of community, reframing the place as merely a party destination. Popularity and limited housing options exacerbate an inflated rental market, with summer 4-bedroom 4-week rate averages exceeding $19,000. Most visitors to The Pines are white gay men who own a home, know someone who owns a home, or can afford to rent for the season. This has resulted in an insular community that runs against current and past movements in the queer discourse, resulting in a less inclusive destination. Additionally, The Pines suffered severe damages following Hurricane Sandy, with flooding impacting most structures. It continues to face existential threats as a barrier island, with significant public resources directed toward dune restoration and breach prevention. The design increases 12-month unit occupancy, benefitting the community economically and culturally in the off season through creative residencies. In peak season, the program changes to tourist-centered housing - connecting visitors with work of the creatives. Changing programs are enabled by a glulam timber structural system which facilitates adaptability from daily user changes to long-term relocation. To improve housing affordability, the design introduces greater density. Slightly taller structures, without compromising neighboring single-family homes, along with adaptive interior partitions allow for higher occupancy in peak months and space for creatives the remaining 9 months.

The Pines is notably inaccessible for the physically handicapped due to its elevated boardwalk system. To address this, every programmatic element has direct access via ADA compliant circulation and has multiple flat connections to the public boardwalk. Due to the stereotypically white, muscled party culture of The Pines, some members of the LGBTQ+ community may still feel that it is not the place for them. So, the design gives agency and privacy to visitors of all backgrounds. Agency over spatial tectonics through movable interior partitions. Agency over social interaction through operable louver systems on public frontages. And privacy by lifting all entrances 12 feet above boardwalk level. The interior courtyard provides an open, social environment for visitors without needing to engage in the scene. Part of the queer influence on Fire Island has been the adaptation of heteronormative single family homes into queer spaces – this attempts to enable a greater level of adaptability from day one. The Army Corps of Engineers has deployed millions of dollars to elevate the nearly 4,500 at-risk structures on Fire Island, which amount to nearly $1.4 billion in property value. The design addresses the growing flooding threat by elevating all first levels and mechanical systems above the NOAA’s 6ft maximum projected flood level. Additionally, all boardwalk circulation can float on guideposts attached to the building structures. The design also reintroduces native trees and plants to the brownfield site, their roots grounding the sandy soil. Long-term, the structural system, informed by the Open Building movement, can be disassembled and relocated. The well-documented longevity of glulam and minimized member sizes enables much of the system to be packed and moved inland. Overall, the design aims to learn from and reinterpret existing social, environmental, and building strategies to introduce a new approach to building community in Fire Island Pines.

STEAM

JON MORRIS | ALEXANDRA MASTERS

H2 OPERATIONS

AUDREY O’BRIAN | KELSEY PIOTROWSKI

Along the Northern East Coast located south of Great South Bay sits Long Island’s much smaller neighbor, Fire Island. Fire Island, NY is notable for its lively atmosphere during the summer, where a party-culture transforms the island. The months of May to August bring the majority of the approximately 2 million tourists each year, many who are a part of the LGBT community. Unfortunately, the high volume of tourists lends to a high volume of waste and harmful practices that put strain on Fire Islands resources and ecosystems. Additionally, due to several yearly severe weather events, the island is prone to severe flooding, which has dramatically impacted the profile of Fire Island over the years. The threats of tourism and future flooding present significant challenges for design and expansion. Fire Island Pines particularly is one neighborhood on the island with the highest risk from these threats, due to its proximity to the ferry station and the significant history it has to LGBT visitors. Currently, all resources coming in and waste going out requires shipments by ferry to and from the island. This is not only expensive, but the carbon emissions for these daily trips will continue to have a growing negative effect on the overall health of the island. Without some kind of environmental intervention, there is a major risk to the existing ecosystems on Fire Island. This is where the role of the H2Operations Center comes into play. Sitting close to the beach in Fire Island Pines, the immediate site experiences a lot of the traffic from summer tourists.

This inspired a unique educational opportunity where tourists are able to stay on site in the nearly 70,000 square foot environmental live-work incubator. Guests are encouraged to tend to the systems in the building that address some of the neighborhoods environmental concerns. When visiting this center, tourists will have a hands-on experience in tending to the aquaponics and hydroponics systems. These systems work in tandem with a floating wetland system that cuts through the building, but also the entire island to allow for the cleaner ocean water to contribute to the filtration of the bay. While the floating wetland system’s primary goal is treating the high levels of wastewater in the Great South Bay, the aquaponics and hydroponics provide fresh foods to be harvested and consumed on site in addition to filtering the water within each tank. Communal style kitchens allow for visitors to harvest from hydroponic and aquaponic tanks to take on an active role in preparing healthier and locally sourced foods.In addition to addressing environmental threats, the center also provides a social space, which is extremely necessary in the busy summer months. In particular, pools and saunas incorporate the water on site into recreational use. The highly public nature of the building allows tourists and residents to mingle and understand their intertwined roles in the health Fire Island. At the H2Operations center, there is equal value given to all–whether tourist or resident, human or wildlife

CASINNOVATION

RACHEL GLANTON | AUGUSTIN GRANADOS

Casinos draw thousands of tourists to Atlantic City, NJ, annually and are responsible for 42% of tourism. However, this form of tourism is insular and separate from the community and local economy. Tourism built on gambling generates a lot of revenue for casino owners and, occasionally, tourists. Meanwhile, the local community experiences economic, professional, and educational disparity. The 2020 U.S. Census also reported a poverty rate for 35%of residents and a median household income of $29,526. The prominence of these establishments also limits economic and job opportunities for residents. According to 2020 U.S. Census data 40% of Atlantic City industries are tourist-centric, such as accommodation, recreation, and entertainment. The existing designs of the casino are deterministic and leave little possibility for adaptive reuse, disassembly, or other strategies that contribute to the long-term functionality of the building. Additionally, game machines reportedly use between 30%-35% of a casino’s electricity. In fact, in 2015, the Wall Street Journal reported that three major casinos were trying to divest from the Nevada grid to keep up their 14 kilowatt-hour per square foot consumption.

As a result, casinos as a typology operate in opposition to the local economy, have a low potential for adaptive reuse, and consume large amounts of energy which greatly impacts the local and global community. A new approach that utilizes the existing tourism economy to decrease economic disparity will increase resident satisfaction and reduce perceptions of government corruption.

Moreover, an increase in infrastructure and city assets will support the future growth of the city. For these reasons, the local government and other stakeholders benefit from addressing how the tourism economy interacts with the local economy and investing in adaptable, energy plus buildings. Our design approach introduces a technology business incubator to Atlantic City. Programmatically, our project reintegrates the revenue from casino tourism with the local economy by using revenue from the casinos to fund start-ups, digital entrepreneurs, and local businesses. Participating entrepreneurs have the opportunity to implement technological developments in game theory, marketing, and risk-taking in the casino, creating a unique gambling experience for tourists. This symbiotic relationship supports job creation, professional development, and emerging businesses while facilitating innovation and an environment in which business owners can study risk-taking, marketing, and social behavior. Additionally, the program supports retail, a resource center, oce space, and innovation lab, event space, entertainment venues, and accommodations making this a true mixed-use development that references the existing context while elevating its positive impact.

To address economic disparity, our design of a mixed-use technology business incubator will contribute to a more equitable socio economic climate, resist urban blight by increasing adaptive reuse potential, and bolster local infrastructure through energy optimization.

GREEN RISE

ASHLEY MEADE | MADDIE RIESTER

Our building proposes a mixed-use development to integrate locals, tourists, and businesses into one area. By integrating locals into this program, we have created affordable housing that can accommodate a single or small family with most of their needs met through the businesses located throughout each building. Since Atlantic City is known for its casinos and large resorts, there is little room for green spaces in the city. In response to this, we have created elevated parks throughout our main buildings. As our site sits at the end of the boardwalk, it was important for our project to become a stopping point and an extension of the boardwalk by reusing the wood.

The site sits near the ocean in Atlantic City, New Jersey, but more importantly, our site sits at the end of the boardwalk, where locals and tourists take advantage of the businesses and views of Atlantic City. The site must respond to this mix of people. Surrounding the site, to the west is one of the large casinos in Atlantic City, and to the east, an empty lot. Within the same zone, the site’s back end has seven small 2-story duplex homes that locals live in.

The city has a total of 4 parks, meaning a park for around every 9,000 people. Our site location is roughly 75,175 square feet, with our proposed building taking advantage of 23,000 square feet, leaving roughly 60% of the lot to an extension of the boardwalk, encouraging people on site. Throughout Atlantic City and many large cities within the United States, the most popular businesses tend to be founded by large corporations, allowing fewer local businesses to thrive in a highly tourist-based economy. Because of this, there is little room for the necessities of locals. This includes local affordable housing, businesses, and green spaces within the city. Research states the importance of these spaces helps control social values and overall well-being for city dwellers. In turn, the architecture of Atlantic City and these cities need to reflect the different types of businesses and their individual needs. In addition, due to large corporations taking over, about one-third of small businesses have been shut down since 2020—specifically, long-time businesses on the boardwalk. However, not all cities engage this mindset toward business placement and maintaining a circular economy.

POLYOPOLY

JOHANNA HILMES | ALEX ROSNO

Atlantic City presents a unique development scenario with a history based in corruption and lawlessness from the gambling market. The existing infrastructure and economic system of the city show remnants of the gambling mecca, though not much else. The city’s decline in population, wealth, and public services for the past 80 years has led to poverty, homelessness, and crime. In the past, Atlantic City was built and developed with only tourists in mind. Previous attempts at reviving the city have followed in the same footsteps, looking to do this with the trickle-down effects of investing in casinos. Polyopoly takes a different approach. The design aims to revitalize the city by creating spaces and homes for the residents of the community, while still acknowledging the importance of tourism in the city’s roots. Situated along the iconic boardwalk, Polyopoly brings the two groups of residents and tourists together in a multi-use residential tower. Constructed out of simple “C” shaped modules, the building acts as an extension of the boardwalk.

The 675-foot vertical neighborhood pulls street-level circulation up and through the 7 “districts” that alternate between residential and public spaces. This alternating pattern encourages interaction and equity among spaces and amenities. Community based programming and housing in one dense location increases the physical and mental well-being of the city by making surrounding spaces more walkable and introducing valuable spaces and programming. Polyopoly creates a sense of community through a design that prioritizes health and sustainability. The building’s commitment to green space and energy efficiency creates enjoyable and affordable living spaces in and around it. Additionally, sea level rise and severe weather are of high concern in this area. The building’s perforations, mechanical system management strategies, and integrated flora make Polyopoly a place of safety and longevity. This skyscraper will give residents a sense of ownership and identity in their home, creating a new perspective for Atlantic City.

ABOVE THE MARSH

MIA WALKER | LUCAS SCHINDLAR

Above The Marsh seeks to solve the disconnect in Sunset Beach, North Carolina, a coastal community that continues to be washed away with rising sea levels and land erosion and a population that is aging and lacking diversity. Our design protects the coast from flooding and erosion with a living shoreline composed of a native marshland ecosystems. In addition, Above The Marsh’s goal is to bring a new tourist that can have an experience through a hostel work exchange along the Intracoastal Waterway that focuses on ecotourism and teaching sustainable traveling habits. With an artificial, but natural protection, the site can provide activities to attract new populations such as agriculture, retail shops, and low impact boating, that would otherwise not be possible on a site bound to be submerged under water within future decades through a series of building, harvesting, and inhabiting from land to sea. Building protection for the community and utilizing local dredged soil and marsh plants to redevelop a marsh ecosystem that has become lost to Sunset Beach. Native species of flora and fauna have become destroyed for housing development and depleted with increased wake activity. The utilization of a living shoreline will bring back these lost ecosystems, and can protect Sunset Beach from complete flooding as sea levels continue to rise. This shoreline will be a complete composition of coastal plants, sediments, and oysters that filter and absorb water, create natural wave barriers, and attract local marine life. Harvesting the site begins following the living shoreline development.

This brings agriculture and aquaculture to the site combining popular economies of inland and coastal North Carolina. These crops are organized based on sunlight and growing properties that rotate through the year, while becoming harvested in offseasons using greenhouses that provide year round produce to the site and Sunset Beach community. Above The Marsh incorporates an aquaculture center to harvest local fish and oyster populations using sustainable methods to avoid overfishing and depleting these ecosystems. Inhabiting the site brings in a population of young travelers that want to give back to the Earth and depleted communities. By providing service jobs on site in various disciplines of agriculture, aquaculture, and restaurant and retail service, travelers can work, while experiencing the North Carolina coast to the fullest. Hostels provide short term stays with immersive views of the developed marsh, while taking advantage of coastal breezes and sunlight to create passive strategies within the units. Above The Marsh creates low impact boating that uses kayaks and paddleboards that create small wakes and low harm on surrounding ecosystems, while completely immersing people within their environments. Each strategy focuses on redeveloping Sunset Beach into a ecotourism hub along the Intracoastal Waterway with protecting and diversifying the depleted community its main goals. Above The Marsh displays how a site can bring populations and activities together that would not be possible until a location is protected as sea levels continue to rise and tourists abuse the places they visit.

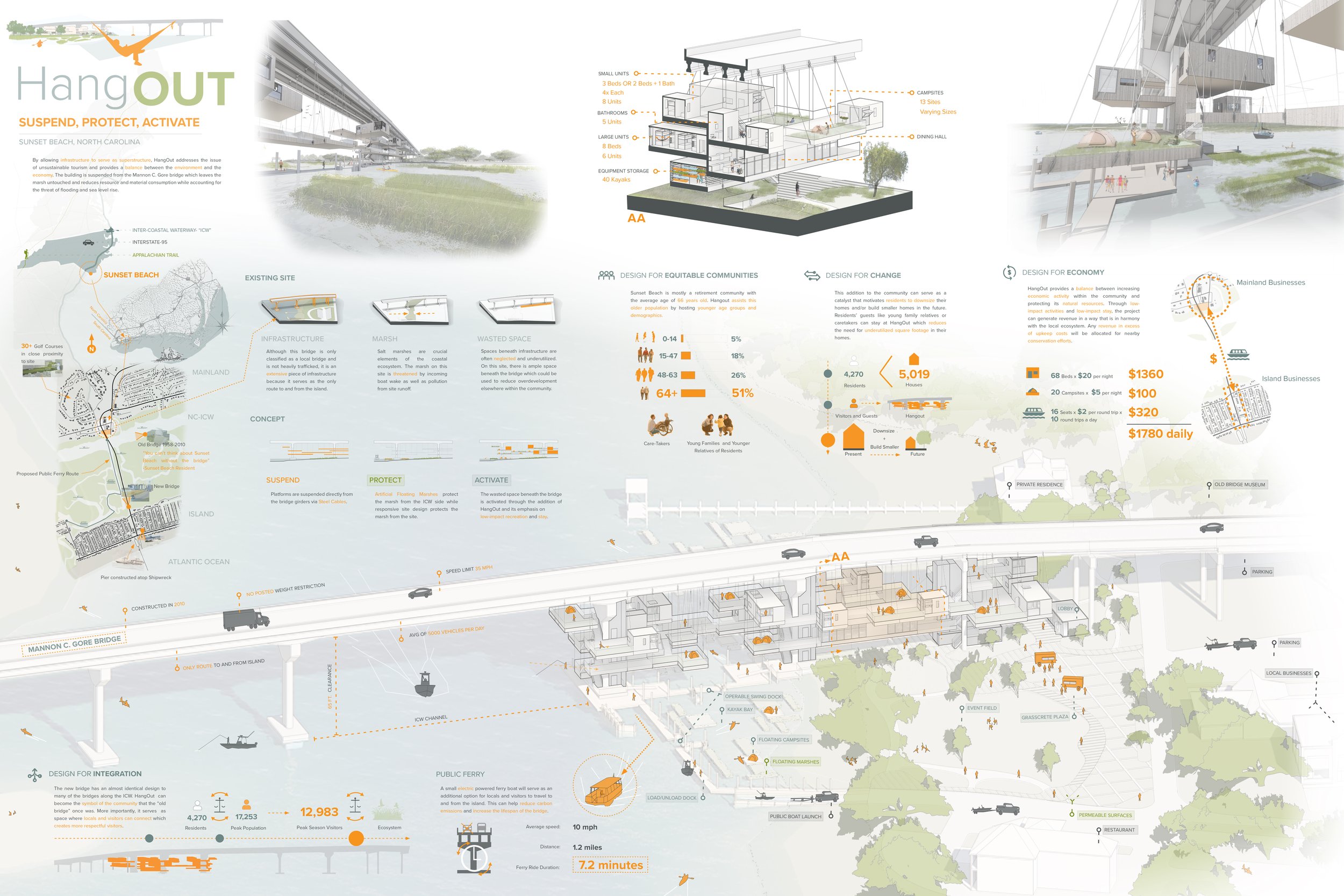

HANG OUT

KEVIN ARNOLD | LAUREL GETTY

HangOut addresses the threat of marsh destruction along the Intracoastal Waterway in Sunset Beach, North Carolina through the motto “suspend, protect, activate”. Communities up and down the east coast of the United States are suffering from the devastating loss of wildlife and indigenous habitats due to over-tourism and reckless development. In Sunset Beach, North Carolina, the marsh along the Intracoastal Waterway is threatened by incoming boat wake and pollution from runoff and is rapidly eroding as native species are becoming endangered.

HangOut is an alternative-stay destination along the Intracoastal Waterway for tourists, locals, and outdoor enthusiasts seeking activities such as camping, hiking, biking, swimming, and kayaking to stay. It is suspended from the Mannon C. Gore bridge, which leaves the marsh untouched while accounting for the threat of flooding and sea level rise in Sunset Beach. Around 30,000 square feet of indoor and outdoor square footage provides unique accommodations for tents, bungalow-style cottages, and hostel-style accommodations for those stopping through. Because Sunset Beach is mainly a retirement community with the average age being 66, current residents can downsize their homes by staying here, with residents’ younger relatives, guests, and caretakers staying with them which reduces the need for underutilized square footage in their homes. Community areas include a check-in space, a dining hall, and equipment storage space for 40 kayaks. Private units are designed to discourage residents spending time in their room and encourage community interaction. Floating artificial marshes are placed along the perimeter of the existing marsh,

protecting the marsh by providing a buffer from boat wake, encouraging new habitats for endangered species, and providing spaces for camping. Bike paths wind underneath the building and along the site among outdoor community spaces for food trucks, outdoor exercise classes, and other outdoor events.

Through sustainable design, this project encourages eco-friendly tourism. Allowing existing infrastructure to serve as the building’s superstructure reduces its overall resource consumption and material transportation while providing the necessary structural capabilities to support the various programs. Facades of units are clad in local wood and a variety of styles of operable windows provide daylighting to interior spaces and allow cross-ventilation to lower reliance on traditional heating and cooling systems. These strategies improve air quality in the building, allow natural air flow, and reduce energy usage and costs. HangOut also serves as a landmark for the community and as a space where locals and visitors can connect. With almost 13,000 visitors in peak season, this serves as a space where visitors can learn about the marsh ecosystem in a low-impact way. A small electric on-site ferry serves as a way for locals and visitors to travel to and from the island, reducing carbon emissions and increasing the lifespan of the bridge. HangOut provides a balance between increasing economic activity within the community and protecting its natural resources. By allowing infrastructure to serve as superstructure, HangOut addresses the issue of unsustainable tourism and provides a balance between the environment and the economy.

SOJOURN

JARED FASSHAUER | PIERCE THOMASON

Located on the mainland side of the Intracoastal Waterway at Sunset Beach, NC, SOJOURN addresses Sunset Beach’s tourism industry, maritime culture, and the many issues it faces, such as erosion, waterfront exclusivity, and pollution.

Currently on our site is a 65 foot overpass that connects the mainland to the barrier island. Previously the only way to the island was a pontoon swing bridge that forced boats to stop and wait in order to continue on. This made our site a stopping point for boaters to hang out while they wait, creating a unique kind of community. This new bridge eliminates that possibility, Sojourn aims to rekindle that.

Marinas are underutilized as stopping points for waterway traffic and community spaces. Individuals of the sailing community, vacationing tourists, and locals can all stay, learn, and grow closer in a resilient marina community that reclaims lost spaces. The overpass is utilized to protect threatened salt marshes by limiting the construction footprint. Tourists will have a place to enjoy, experience, and play together in a re-imagined marina that re-engages the public to the waterway. This Marina thoughtfully repurposes dredged material taken from the shallow Intracoastal, and reinforces eroding shorelines which help protect salt marsh ecology. Areas including lodging, community gardens, dining options, waterfront activities, food gardens, event space, and a marketplace are all connected to the waterway by boardwalks that act as a continuous, three-dimensional dock.

DOWNPOUR

MYLIAH BOYD | JESSE PARKS

The site is St. Helena Island, which is located on the southern coast of South Carolina. It faces several important issues regarding ecological and cultural health due to the arrival of tourists every season. With a total square footage of 12,531 square feet, the project is small but purposeful in blending in with the surrounding context.

By focusing on integrating tourists with locals from the area, we hope to emphasize the community’s culture- which is extremely rich due to the Gullah Geechee heritage on the site. This project focuses on celebrating intense and temporary moments of sudden saturation like heavy rainfall and the influx of tourists. We do this by collecting, filtering and utilizing.The site sits along the gullah geechee heritage corridor, and more specifically, walking distance from the Historic Penn Center Campus, which is home to the first school in the south for formerly enslaved West-Africans. Today, the campus functions as an educational and cultural center. We knew that our project and program had to interact with this significant context, and this set up our figure ground and created the central axis along the site. The project responds by working with the existing program of the Penn Center and seeking to be an extension of it.

Our project responds to many of the existing Gullah Geechee traditions and hopes to encourage the education and passing on of these important cultural values. The most critical part of this project, when looking through the lens of design, is the roof. We designed this canopy to function in many ways. One function being sun protection and shading, where the top of the roof reflects unwanted heat gain. Another function is letting natural light in the buildings through skylights, with PV panels filtering the Southern light and producing electricity for the building. And the most important concept of the roof is collecting rainwater.

ROOTED: DE’ GULLAH GEECHEE HOST COMPOUND

ANDRE DANIELS | CIERRA DAVIS

Located on St. Helena Island, South Carolina, De’ Gullah Geechee Heritage Compound is a response to the encroachment of ecotourism which threatens the Gullah Geechee. A Nation of people located along the Gullah Geechee Corridor, which stretches from Jacksonville, North Carolina to Jacksonville, Florida and includes the Sea Islands to 30 miles inland, the Gullah Geechee are a people who have origins through the Transatlantic Slave Trade, as well as indigenous roots to the Americas. They were swiftly freed in 1862 with the Union occupation of the Sea Islands, and on St. Helena Island, the Penn School (now the Penn Center) was established to educate the newly freed slaves in trades in order to assimilate them into American Society. Our approach to the threat of ecotourism on St. Helena Island will address a few issues: a lack of homeownership, the negative effects of heir’s property laws, and the island being a food desert. Encroaching tourism and development have led to cultural losses and dilution of the Gullah Geechee in the surrounding Sea Islands and areas (think Hilton Head Island, Edisto Island, Charleston, South Carolina, just to name a few). Our site sits 2,000 feet away from nearby marshland, where the sweetgrass used by the Gullah Geechee to meticulously craft their famous sweetgrass baskets grows abundantly. It also sits directly adjacent to the historic Penn Center, the first school for freed slaves in the United States, established in 1862. It now serves as a cultural center for the Gullah Geechee, having recently celebrated 160 years of existence.

Our site will serve the Gullah Geechee community, and our design is modeled after the traditional settlement style of compounds, which is comprised of a cluster of homes, typically family members, all around a shared garden. Our approach modifies and modernizes this settlement style. Our compound is a live-work environment, where businesses are on the ground floor, residences are on the top floor, and rooftop gardens sit atop each structure. Our businesses include a crafts and essential goods store, a barbershop and beauty salon, a familyowned restaurant, a market, and an advocacy unit to address heirs’ property, which has plagued the Gullah Geechee and African Americans living throughout the rural Southeastern United States. We have residential units for each business, as well as 2 additional units. Lastly, we have implemented a host program, where tourists can come stay with families and become immersed within the culture; also, we have 3 tourist units where tourists can also stay privately. Overall, our intention is to create a space unique to the Gullah Geechee culture, where their customs, traditions and practices can be preserved through their own expressions without the threat of being diluted by threats of ecotourism and development.

THE CRAFT, THE TRADITION AND THE CELBRATION OF CULTURE

OLIVIA WIDEMAN | ANGELA KRAUS

The Craft, the Tradition, the Celebration of Culture, aims to solve the disconnect between culture, place, and estranged descendants through an immersive, hands-on learning center that celebrates the trades and traditions through practice. The area spanning from Jacksonville, FL to Wilmington, NC is known as the Gullah Geechee Heritage Corridor. With the rise in development and tourism along the coast of South Carolina, the ecosystem is on the brink of an environmental disaster. The increase of storms and flooding is detrimental to the environment that was once self-sustained. St. Helena Island is the last South Carolina Sea Island along the corridor where the Gullah still lives and practices. The sea islands and culture are at risk of vanishing completely if traditions are not practiced and passed down to younger generations. Self-identity strengthens character and confidence. When children have a deeply rooted understanding of their heritage, their self-worth is increased. Studies show the most impactful age range for character development is between the 2nd and 8th grades. Trades and traditions from locals are passed onto students attending the 7-day heritage program, in hopes to strengthen cultural identity and self-importance. Situated across from the site is the Penn Center. This historical campus became one of the first schools in the country to provide a formal education to previously enslaved West Africans. Today the center serves as a museum, community center, and historical landmark.

Agriculture, cuisine, build + restore, art + folklore are the four programmatic approaches, each of high value to the culture and resilience to the direct community and environment on St. Helena Island. Re-introducing Carolina gold and a vegetable garden allows for year-round interest to inspire education. Students learn about the process’ of soil preparation, sewing seeds, maintaining, and harvesting crops. Once harvested students create Gullah dishes with the three traditional methods of cooking: grilling, stewing, and wood burning. Other methods of cuisine include preparation and preservation, from deshelling and creating spices, to canning and salt-curing. Outreach donates excess crops and meals to local markets for profit. Students learn traditional construction methods and blacksmithing in the tool shop. In the material shop students learn processes of harvesting, carpentry, and joinery, as well as creation of the vernacular material. Outreach consists of repairing and building structures on the island. Students experience folklore and language through immersive guided tours along the site. Students learn traditional song, dance, and instruments during their stay. Outreaches include festivals where students can sell and celebrate their crafts. Lofts are playfully incorporated in each zone to spark a sense of discovery and immersion. Each zone incorporates unfolding furniture elements that support the learning experiences, as well as indoor-outdoor classroom spaces that fully immerse the student in place.

EMBRACE

LYDIA GANDY | MICHAEL URUETA

Operation explores ways to adapt and reuse materials as well as structural systems from a former coal production plant and uses them to implement new building technologies to support a self-sustaining community. Operation is located on the site of the former Kanawha River Plant along the Kanawha River in Glasgow, West Virginia. This post-industrial site falls within a climate zone with average temperatures ranging from 15 to 90 degrees fahrenheit. The site contains an existing railway, coal plant, and 56,000 cubic feet of post-production fly ash across its 120 acres of land. The Kanawha River Plant once served as a centerpiece from which all means of livelihood were provided such as jobs, housing, and food for the local coal miners in the adjacent town, known as the Town of Glasgow. However, in 2015, the plant shutdown resulting in the loss of jobs and housing causing the community to become stagnant and deteriorate.

In lieu of this, Operation aims to reimagine the coal industry and replace the culture of extraction with a cleaner, safer, and sustainable environment to reactivate the town and provide a new sense of purpose to its community members. Through the use of Gantry Systems from the former coal plant, the project implements 3D Printing Technology to provide affordable housing solutions, jobs, as well as can be adapted into systems for growing and harvesting food. Our site by the numbers can produce 3.6 million kWh of electricity through the use of wind turbines, 588,000 lbs of food per year over our 50 acres of farming land, and reduces construction waste by 90% with the use of 3D Printing. The existing railway provides means of transportation for people and moves materials to and from the site. By repurposing the gantry systems, the project aims to create a self-sustaining community that can not only provide for itself, but serve its neighboring community and set a precedent for future coal mining sites along the Kanawha River.

IMMERSE

OSAMA HASHEM

Saint Helena Island in South Carolina is home to the Gullah Geechee people, who trace their roots back to Africa and have their own culture and traditions. The island of Saint Helena makes the Gullah Geechee people more accessible to tourists, which leads to conflicts and tensions between tourists and permanent residents. The island of Saint Helena lies at the intersection of environmental and social justice efforts, with Gullah Geechee communities experiencing increased exposure to cultural and environmental threats.

Current threats facing the Gullah Geechee residents can cause the erasure of the community and its significant cultural contributions. Furthermore, environmental threats are danger to all who live in (humans, flora, and fauna) and visit the area. It is important to integrate permanent Gullah Geechee residents and tourists together to achieve harmony and the continued exchange of knowledge. Historically, cultural preservation has not always been implemented through a DEIJ (Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Justice) lens. In order to protect the Gullah Geechee community, all conservation efforts must be inclusive for all, account for the community’s rich cultural diversity, and ensure equitable and just processes when integrating the two populations together.

This will allow for a sustainable solution and will aid in the preservation of the local Gullah community’s culture and traditions. Also, it will support the Gullah community’s local economy through the sale of their local products and cuisine and help develop sustainable practices to protect against environmental and social threats and enhance the natural landscape. How can architectural design find solutions to the problems between tourists and the local community? The Immerse project will help and support the local community and tourists by providing a space for activities where people of all ages can learn, work, and gather together in a sustainable way. The project has three floors with different functions and uses. The first floor includes single-day and multi-day workshop spaces and the market, the second floor is the conservation center, and the last floor is where visitor residency rooms are located. This project is the solution to the conflicts and tensions that have risen between the Gullah Geechee people and tourists.

THE MISSING PIECE

DIVYA AGRAWAL | PEYTON DAVY | MORGAN SHAWEN

This project is located in the neighborhood of Bahama Village, a neighborhood in Key West, Florida with a long and rich culture that has so far lasted the test of time. The residents have ancestors from Cuba who escaped to find freedom, the Bahamas who found a better life in the Keys, and Africans who escaped from the slavery taking place on mainland Florida. This neighborhood serves as a melting pot, bringing everyone together and blending their cultures, while still keeping key features from each.

The biggest problem our building addresses is that many locals are moving away and with that, their culture is slowly fading. We broke this into three main problems which were: many employees in Key West have jobs ties to the 4-month tourist season, as tourists move in and buy vacation homes, locals can no longer afford the area, and a lack of greenspace or outdoor gathering space.

This is addressed through affordable housing, multiple job opportunities throughout the buildings, and a variety of outdoor spaces. For example, the on-site house was renovated into a restaurant and teaching kitchen.

Our building secondarily addresses sustainability by using a shading system and cross-ventilation. There is also a food system that begins with the green roof collecting water, the water being used in the garden, the garden’s produce being used by the restaurant and by locals, and the waster going back to compost the garden.

CONCH COTERIE

MAKAYLA CLINE | STACY KNIGHTON

The cost of living in Key West has gotten out of control. Bahama Village is known as one of the poorest neighborhoods in Key West, however properties are listed for over 2 million dollars. These properties are being purchased as second homes for wealthy people. This pattern of purchasing vacation homes is forcing locals, most who have lived there for their entire lives, to either move out of the Keys or commute a very long distance for their job in the service industry. Majority of the locals in Bahama Village have service industry jobs and make less than $38 thousand per year which makes it impossible for them to continue living in the place they call home. Though the economic growth of tourism is funding the lives of many locals, the overpopulation of tourists, leading to vacation homeowners and seasonal visitors, is negatively impacting locals in Key West, specifi cally Bahama Village.

To address this problem, we have designed a self-sustaining, affordable housing complex that accommodates the users needs by providing basic needs all within the site. Our site is located within the Bahama Village community in Key West, Florida and our typical users are service industry workers who work in restaurants, retail stores, or cruise ships. The family types we accommodate vary from single individuals, single parents with one or multiple children, or couples.

The program we have included to cater to the users of the project are 3 different unit types depending on family size, childcare, gym, game room, shared kitchen and living areas, outdoor kitchen and living, laundry facilities, cafe, as well as a community center that has gathering space for the Bahama Village community and an area to display crafts and artwork of the local community.

To address the environmental and self-sustaining needs of our project we are including a rooftop garden that grows local vegetables to feed those that live there and a marketplace to sell the surplus to the Bahama Village community. We also areincluding a rainwater collection system for non-potable water, PV panels to help power our site and we plan to place operable windows strategically throughout our facade to eliminate the need for HVAC systems. On top of the windows we will have operableshutters that can be used during a normal day to let air in through with the window open and to be used a storm shutters during severe weather or hurricanes with the windows closed.

By designing self-sustaining and affordable community housing we are reducing the number of locals leaving the area due to infl ux in the cost of living. This project implements passive design strategies such as solar energy, wind, and rainwater collection and has a focus on equitable community and well-being of the occupants. This is shown through creating a sense of belonging and providing a high quality of life for those living in the community. This will limit the pressure put on locals to relocate and increase the number of local service industry workers in Bahama Village by giving them a reliable place to reside regardless of the tourist season

THRIVE

HADLEY DOWNARD | NATALIE WADE

Located in the florida keys as a historically underprivileged community within a bustling tourist destination, thrive exists to change the self-serving lifestyle of tourism. By providing a unique community space that welcomes locals and tourists to participate in self-sustaining food practices, we can aim to mitigate issues like a lack of affordable housing, and inconvenient fresh food options for those who need it most in this area.Although 78% of key west is white, approximately 11 % of key west lives in poverty, and 32% Of those residents are African American. Bahama village sits in a low-income area, colliding with the demands of tourism, a culture where cost of living is unreasonably high. With inflation, rent will only escalate, increasing the urgency for new affordable housing solutions in this area. Additionally the development of tourism in key west has constrained bahama village and resulted in a food desert. The closet two grocery stores stocking fresh food range from 0.8 -1 Mile away from the site making it realistically inaccessible by biking or walking. Food deserts present a problem to the health and wellbeing of those who are living in the area.

A lack of fresh and healthy food choices is known to negatively impact ones health. Research shows that “a key concern for people who live in areas with limited access is that they rely on small grocery or convenience stores that may not carry all the foods needed for a healthy diet ... Many studies find a correlation between limited food access and lower intake of nutritious foods” (ver ploeg, 2009). This project aims to cultivate a culture of self-sustaining food practices and regenerative, selfless tourism. By producing and selling food on site, our project will provide bahama village with the much needed fresh and health food options that are currently inaccessible. With food production weaved throughout the site and in central spaces, thrive offers a place for locals, residents and tourists to interact with the food they eat and with each other. Thrive sets the vision for all who visit to consider how they can help the community around them, and displays the difference that can be made.

MICRO ECO BREW

HAYDEN HOLT | AUSTIN LEMERE

Cherrystone RV campground, located in Northampton county Virginia, draws in thousands of visitors each year. The region celebrates its coastal and agricultural resources, holding regular farmers market events, and has a healthy appreciation for local seafood, particularly oysters. However, Cherrystone is disconnected from that community at nearly a ten-minute drive from any town center. The project is an environmentally-conscious craft brewpub and tourist lodging complex intended to invigorate the existing community, integrate a positive tourist atmosphere at a newly corporate camping destination, and immerse visitors into the native coastal marsh ecology of the site. Cherrystone RV campground is a symptom of a larger tourist culture among RV camping destinations which contributes to negative impacts on the environment such as habitat loss and deforestation.

The project anticipates sea level rise on its fl at coastal site, and incorporates a symbiotic water cycle and ecological processes as design strategies in an effort to mitigate and reshape an industry that has historically disregarded its impact on climate change and habitat destruction. The brewpub will utilize local resources in the brewing process, including on-site farming of hops and sourcing from nearby barley fi elds, in an effort to support the local economy and promote agritourism. The goal of the project was to expose this process to users of the site, drawing them in with a unique program and well-performing buildings, with the hope that they leave feeling more educated and connected to the two things this region values most: the coastal marsh and the agricultural community.

RECIPROCITY

NAUTICA EDGE | MICAH HOLDSWORTH

Agritourism in Cherrystone, Virginia has been the method in which the town operates for generations. With Recreational Vehicles at its core, this current model of tourism fragments the landscape, fails to protect biodiversity from invasive species, and pollutes the very salt marshes that facilitate the region’s economy of agritourism and farming. In response to these existing issues, Reciprocity proposes a model of tourism where users experience a full embrace of the natural environments on an indigenous level that not only engages users with the wetlands but indulges them in a system of exchange with the land; as tourists care for the land through long-term management, it provides a place for them to live.

The project proposes an insular, self-sustaining model of agricultural tourism revolving around the cultivation, harvest and processing of cattail and the use of cattail goods to build tourist cabins over time. Located in an existing coastal RV camping community, our project facilitates a healthy exchange between the tourist and the site by involving campers in every system that sustains the built and natural environment’s health. This curated educational and contributive experience has the tourist engaging in research on wetland health and water-treatment, harvesting cattails in each season for the various goods they provide, and pre-fabricating cabins with cattail-based materials that are processed and produced on site. Harvested cattail stems can be stripped, glued together with magnesite and hot pressed to produce Typhaboard, an OSB-like innovative material with comparatively far superior structural, insulative, acoustical and weather-resistant attributes.

The various site systems and productions are monitored, researched, and iterated on yearly, leading to a natural innovation and improvement in cabin design, wetland health, and tourist experience. A board walk weaves throughout the site, integrating each component of the natural cycle. The Wetland Research Center on site addresses the lack of current bay research on the aff ects of human interactions on the health and wellness of the bay and wetlands. This center not only investigates bay health but seeks to restore the coastal wetland adjacent to the site. Campers enter into the site through The Ecology Center, and are able to retrieve all supplies for harvesting and site immersion. The tidal canal hosts a wetland that is home to several phytoremediators such as cattail that are restoring the salt marshes along the coast of the Chesapeake Bay. To limit the amount of fragmentation in the environment, the cabins are constructed in an area near the back of the site called the Production Pavilions. Here, harvested cattail is processed into Typhaboard SIPs which are used in the construction of the cabins. Excess Typha-material is used for crafts and other activities in the ecology center as well as recycled into compostable material, and the rhizomes are taken to the research center to be stored for replanting in the spring. Whereas the site had previously been fragmented by gravel roads for RV camping, now elevated prefabricated cabins allow for the natural ecology to flourish uninterrupted throughout the site.

INTERTWINING

DIVYA CHARGULLA | KAYLA PRATT

Our site is an RV campground in Cherrystone, Virginia, directly on the Chesapeake Bay. Our project, named Intertwining, is primarily constructed above the RVs on the site. With thirty-four cabins, five communal kitchens and one greenhouse, our site has a combined total square footage of 19,740 square feet. The site floods frequently2 and, due to sea level rise, could be submerged within 80 years1. This poses a great threat to the site’s longevity. Our goal is to preserve the site’s existing use, while also creating a new system that allows the site to be used when the site is submerged in water. Therefore, the elevated cabins are connected to the communal kitchens via a tree walk which will allow for navigation of the site even while it is flooded. The communal kitchens, greenhouse, and five ground level cabins all have an amphibious structure. This allows the structures to float with any water that enters the site. There are also seventeen RV lots that will have an amphibious foundation to allow the RVs to rise if there was a sudden flood. These platforms could be used for tents as the sea level rises and eventually have cabins constructed on them and then connected back to the tree walk. The greenhouse and oyster farm on the site aim to incorporate the surrounding community and its strengths.

The greenhouse and oyster farm will provide food for the users who will work with local farmers and the nearby aquafarm to produce and harvest the food. Each cabin and communal kitchen have large openings to allow for natural ventilation, as well as encouraging users to open the indoor spaces to the outdoors. The southern facing roofs are covered with photovoltaic panels, and the northern facing roofs are treated with a tray system green roof to slow stormwater runoff. The green roofs also help to maintain the buildings’ temperature. Each building also has a hydronic floor system that is heated by geothermal heat pumps. As the water level rises, the site’s accessibility and uses will change with it. The tree walk would function not only to navigate the site, but also as the main structure that all activities would stem from. Users would use the tree walk as a dock for their boats, kayaks, and any other modes of water transportation. It would serve as the main place to produce oysters and each cabin could have its own small oyster farm. The activities on the site would be more water related and the water harvested from the roofs would become more important to produce food. Intertwining adapts the current Cherrystone RV campground by creating a new system elevated above the old one. This is respectful to the site and its current users while also allowing the lifespan of the site to be extended.