2019 | LOST SPACES

Architectural solutions for leftover space created by America’s elevated urban highways

David Franco | Ulrike Heine | George Schafer

FOREWORD

The construction of the American interstate highway system during the post-World War II era transformed the physical, social, historical and cultural fabric of cities across the country. The reverberations of this massive infrastructural network on the built environment – the loss of a land ethic, the advent of urban sprawl and the rise of the American suburb, significant and sustained central city population decline, and the wholesale destruction of predominantly lower-income and minority urban communities, to name a few – resulted in a paradigm shift for the disciplines of architecture and urban design that are still being felt well into the 21st century. With a renewed focus on urban renewal and creating more accessible, livable and integrated cities, the leftover, seemingly uninhabitable spaces underneath and adjacent to the massive concrete ribbons of interstate that snake through America’s cities – often referred to as lost spaces – present unique opportunities for urban reclamation and repair. As most cities contain vast quantities of these leftover spaces, vague on purpose and seldomly integrated into formal planning and design, lost spaces present one of the last frontiers of unexplored urban development.

Some American cities have begun to reclaim their urban spaces lost to the interstate system, largely through infrastructural-scale remedies, such as the Big Dig in Boston, Massachusetts. The formula: submerge the elevated interstate, reclaim the ground plane, and repair the urban fabric. However, the vast majority of urban elevated interstate highways are likely to persist, presenting opportunities for architects and urban designers to leverage the many strands of place-making, environmental stewardship, social equity and economic viability toward the transformation of lost spaces into places with distinct, harmonious beauty and identity. The studio presented in this publication, which took place at Clemson University during the Fall 2019 semester, explored lost spaces in four American cities – Portland, Oregon; Denver, Colorado; Dallas, Texas, and Louisville, Kentucky – by interrogating the intersection between housing and urban infrastructure. The projects presented herein are optimistic about the symbiosis that can be achieved between the interstate, the city and its inhabitants, and illuminate integrative design strategies for effectively stitching dormant interstitial zones back into the physical, cultural, economic and experiential condition of the American city. and its inhabitants, and illuminate integrative design strategies for effectively stitching dormant interstitial zones back into the physical, cultural, economic and experiential condition of the American city.

Introduction

PROJECT BACKGROUND

This studio will explore architectural proposals for leftover spaces that are the byproduct of elevated urban highways. Completed between the late 1950s and the early 1970s, the interstate highway system had powerful and almost inevitable consequences for America’s urban environments, often creating seemingly uninhabitable zones and problematic discontinuities in the physical and social fabric of cities. These vast quantities of leftover spaces are seldom integrated into formal planning and design. Vague on purpose, the interstitial spaces have been referred as lost spaces. The lost space along and under elevated highways affect the way we experience the city. These spaces create disconnected neighborhoods, produce undesirable views, and act as physical and psychological barriers to urban connectivity and cohesion. America’s reliance on vehicular transportation creates increased levels of sound and air pollution along urban highways, resulting in a wide range of health risks that limits the potential of lost spaces as opportunities for urban growth and development. Moreover, the unclear territoriality of these spaces often leads to land misuse, leaving areas adjacent to urban highways susceptible to the dumping of waste, vehicular abandonment and other illegal activities. Rather than accept the marginalization of lost spaces as inevitable, this studio aims to explore these urban interstices and will investigate their potential as opportunities for urban reclamation and repair.

As part of the studio we will work in the preparation of the AIA COTE Students Competition and will leverage the conceptual frame of the competition toward architectural solutions addressing the persistent problem of urban lost spaces. The AIA COTE framework will force unapologetic, if not radical, architectural responses to the question: (1) How can abandoned, polluted and largely unusable leftover space adjacent to America’s urban highways support the design of high-performing, equitable and beautiful buildings? Design solutions that successfully answer this question will attend to issues of climate, health, technology, space and culture – and will reveal strategies for reparation of interrupted urban fabric in America’s cities. To that end we have selected four sites – segments of elevated urban highway – in four American cities, specially chosen to put in play the questions proposed by the competition brief as well as the general theme of the studio.

GENERAL THEME

While envisioned as a catalyst for economic growth and freedom for America’s cities, the interstate highway system has had a persistent, uneasy relationship with the urban environment from its inception. Raymond Mohl (2002) elaborates on this tension in his paper entitled “The Interstates and the Cities: Highways, Housing and the Freeway Revolt:”

“Few public policy initiatives have had as dramatic and lasting an impact on late twentieth century urban America as the construction of the interstate highway system. Virtually completed over a fifteen year period between the late 1950s and the early 1970s, the new interstate highways had powerful and almost inevitable consequences. In metropolitan areas, the completion of urban expressways led very quickly to a reorganization of urban and suburban space. The interstates linked central cities with sprawling postwar suburbs, facilitating automobile commuting while undermining what was left of inner-city mass transit. Wide ribbons of concrete and asphalt stimulated new downtown physical development, but soon spurred the growth of suburban shopping malls, office parks, and residential subdivisions as well. At the same time, urban expressways tore through long-established inner-city residential communities in their drive toward the city cores, destroying low-income housing on a vast and unprecedented scale. Huge expressway interchanges, cloverleafs, and access ramps created enormous areas of dead and useless space in the central cities. The bulldozer and the wrecker’s ball went to work on urban America, paving the way for a wide range of public and private schemes for urban redevelopment. The new expressways, in short, permanently altered the urban and suburban landscape throughout the nation. The interstate system was a gigantic public works program, but it is now apparent that freeway construction had enormous and often negative consequences for the cities” (p. 2).

Mohl highlights the fundamental contradiction of the interstate system: While vehicular infrastructure has contributed to the expansion and economic growth of American cities, it has also negatively impacted many communities, especially low-income and minority neighborhoods physically separated and isolated by stretches of elevated urban highways. Most cities have done nothing to repair the damage done to these communities. However, the trend toward densification of America’s urban centers mandates that the lost spaces beneath and adjacent to elevated vehicular infrastructure can no longer be an afterthought. These sites arguably encompass one of the most blighting influences on many American cities – and yet they also constitute one of the last development frontiers. This studio will view lost spaces as an untapped urban asset – and will explore architectural solutions that aim to mitigate the environmental, physical, social and cultural barriers to their successful reintegration into the urban fabric.

SITE CONSIDERATIONS

The four cities/sites for intervention reveal many examples of lost spaces – unused, disconnected and underdeveloped urban fragments created by an adjacency to a segment of an elevated urban highway. These four highways are among those featured in the 2019 Congress for the New Urbanism list of “Freeways Without Futures,” and represent problematic conditions within their respective urban fabrics as well as promising opportunities for urban reclamation and repair. Each site is unique in its climatic, cultural and morphological condition. Students are encouraged to research the lost spaces within the site boundaries as presented for each highway segment and make a claim about the sites where architectural intervention can be most impactful and reparative.

Interstate 5 | East Portland, OR

I-5 segment bound by the Willamette River (W), SE Water Avenue (E), the Oregon Museum of Science & Industry (S) and SE Taylor Street (N).

Interstate 64 | Louisville, KY

I-64 segment bound by N. 12th Street (W), N. 6th Street (E), W. Main Street (S) and the Ohio River (N).

Interstate 345 | Dallas, TX

I-345 segment bound by Cesar Chavez Boulevard (W), Good Latimer Expressway (E), Canton Street (S) and Gaston Avenue (N).

Interstate 70 | Denver, CO

I-70 segment bound by the York Street (W), Steele Street (E), 45th Avenue (S) and 47th Avenue (N).

While the Congress for the New Urbanism’s “Freeways Without Futures” project focuses primarily on the replacement of these highway segments with on-grade boulevards or underground highways, this studio will instead confront the elevated highway segments as persistent yet adaptable physical artifacts and will explore how architectural interventions, in tandem with the existing vehicular infrastructure, can serve as catalysts for the reintegration of lost spaces into the urban fabric. While each design proposal should emerge from, address and resolve site-specific conditions, successful projects will also serve as design exemplars – case studies that illuminate strategies for effectively stitching dormant interstitial zones back into the physical, cultural, economic and experiential condition of the city. Think: New architectural intervention + existing elevated highway = new building typology.

CENTRO DE SALUD

CELIA GANNAWAY | COURTNEY WOLFF

REIMAGINING HEALTHCARE IN ELYRIA SWANSEA, DENVER CO. Along the major Interstate 70, spanning from Utah to Maryland, in Denver, Colorado we see an escalating asthma rate with declining accessibility to simple health-related resources. There is a divide created in the neighborhood of Elyria Swansea. Not only should architecture bring a crippling community together, it should serve as a tool to promote healthy environments to strengthen the identity of a community. Something needs to be done about Denver’s heightened pollution rates, this neighborhood specifically with its booming industry and populous interstate looming overhead. Elyria Swansea, Denver has the highest environmental hazard risk of over 8600 zip codes nationwide. A proposed campus for this site provides an innovative solution to health-care in a weakening community. With an aging community, and a majority Hispanic population, Elyria Swansea needs an alternative to traditional senior adult care. This development must provide a retreat and resource for the aging population without prompting isolation. This will improve the medical and psychological state of its users and encourage them to live a healthy lifestyle through an increased quality of life. Centro de Salud is

located in climate region 4. A semiarid climate with cold, windy winters and warm, dry summers. Annual precipitation is 17” compared to a national average of 38” annually. Buildings are clustered together to minimize the number of exposed walls to keep heat in and cold out in winter. Buildings are also tucked under the existing Interstate to provide shelter without the use of additional raw materials. Windows and trees are minimally placed on the South sides of buildings to let the winter sun in. Trombe walls on the South are effective for passive solar heating in the summer months with green roofs to insulate in the cold winter months. By integrating the architecture with the colloquial style of Elyria Swansea, and by implementing site-specific ecologies and pollution technologies as well as the implementation of a public courtyard and elevated running track, the user’s health and wellness will be improved through the promotion of social interaction in the community. The architectural proposal contains 8 assisted living units, a shared living and dining building, a 24/7 healthcare clinic, and a gym equipped with workout classrooms totaling at nearly 20,000 square feet.

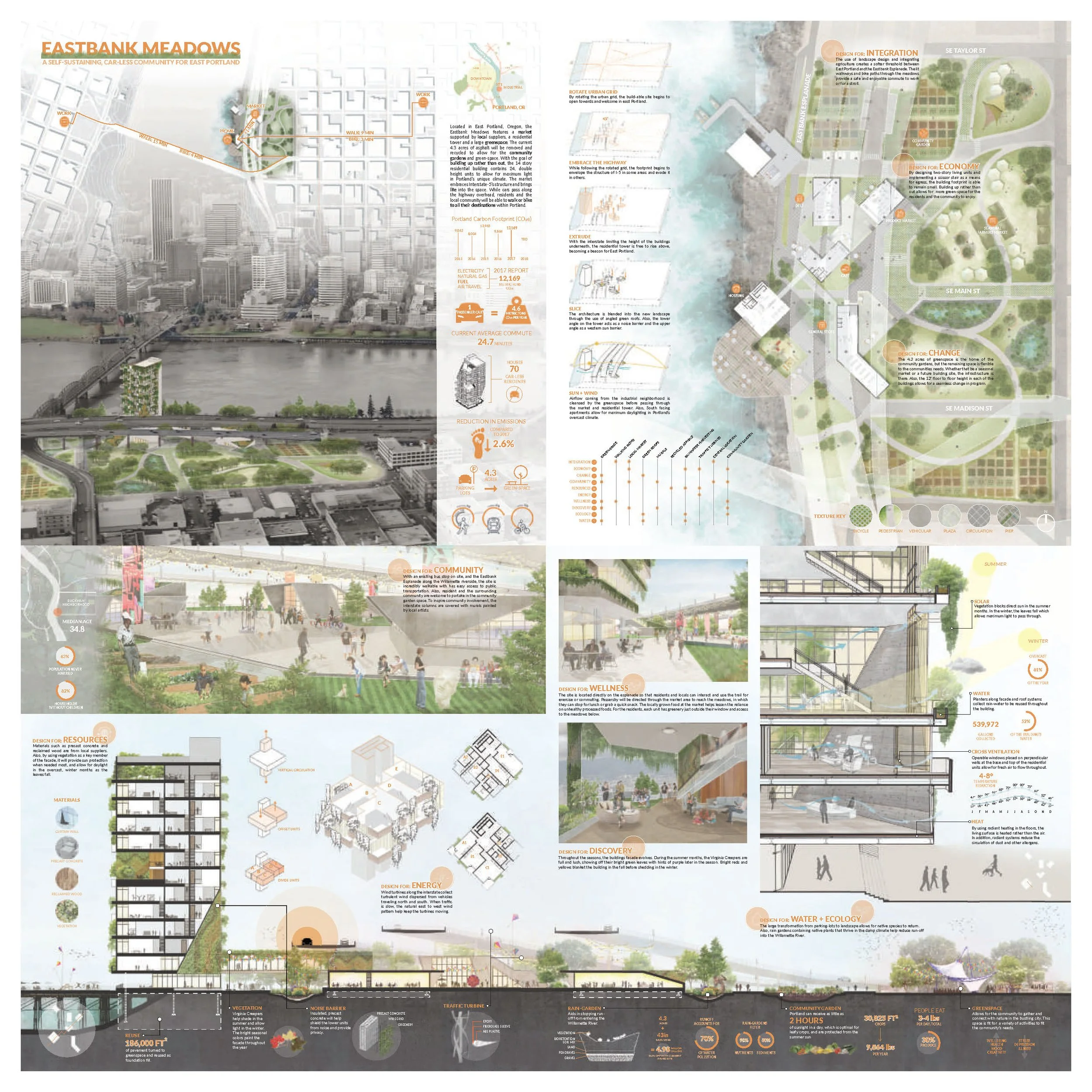

EASTBANK MEADOWS

SARAH SMITH | UNIZA RAHMAN

Located in East Portland, Oregon, the Eastbank Meadows features a market supported by local suppliers, a residential tower, and a large green-space. The current 4.3 acres of asphalt will be removed and recycled to allow for the community gardens and green-space. With the goal of building up rather than out, the 14 story residential building contains 24, double-height units to allow for maximum light in Portland’s unique climate. The facade features a variety of vegetation to aid in interior temperature control. This alive and seasonal facade paints the residential building bright red and yellow in the fall and has purple blossoms in the spring, which helps connect the residents and the community back to nature’s colorful cycle. The wet climate allows for the vegetation to thrive, and when the leaves fall in winter, they can be used for fertilizer in the gardens. The market embraces Interstate-5’s structure and brings life into the space. It will be a one-stop-shop for residents and the local com-munity for meals, groceries, and household needs as well as a gathering space. While cars pass along the highway overhead, residents and the local community will be able to walk or bike to their destinations within Portland. As the site stands, there is an incredible harsh threshold between the people of east Portland and the Eastbank Esplanade. The use of landscape design and integrating agriculture softens that threshold and welcomes in the locals and provides a space for gathering and activities. The lit

walkways and bike paths through the meadows provide a safe and enjoyable commute to work or for a stroll. By designing two-story living units and implementing a scissor stair as a means for egress, the building footprint is able to remain small. Building up rather than out allows for more green-space for the residents and the community to enjoy. The 4.3 acres of green-space is the home of the community gardens, but the remaining space is flexible to the community’s needs. Whether that be a seasonal market or a future building site, the infrastructure now exists. Also, the 12’ floor to floor height in each of the buildings allows for a seamless change in program. With an existing bus stop on site, and the Eastbank Esplanade along the Willamette riverside, the site is incredibly walkable with has easy access to public transportation. Also, residents and the surrounding community are welcome to partake in the community garden space. To inspire community involvement, the interstate columns are covered with murals painted by local artists. Materials such as precast concrete and reclaimed wood are from suppliers located just a few blocks away from the site. Also, by using vegetation as a key member of the facade, it will provide sun protection when needed most, and allow for daylight in the overcast, winter months as the leaves fall.

ELEVATED INTEGRATION

GEORGE SORBARA | HUNTER HARWELL

“Elevated Integration” is a direct response to Portland, Oregon’s growing number of families facing homelessness. As of 2019, there were 4,015 individuals facing chronic homelessness within Portland. Seventeen percent of those individuals, including 374 children, belong to a family that is facing chronic homelessness. The necessity for a response to this situation is imperative and the very essence of “Elevated Integration” at its purest form. “Elevated Integration” is also an architectural response regarding the leftover spaces that are a byproduct of elevated urban highways. From uninhabitable zones to discontinuities in the urban and social fabric of cities, the interstate highway system has had seemingly irreversible consequences for America’s urban ecologies. “Elevated Integration” is a design solution to support a marginalized population of homeless families while simultaneously mending a discontinuity within a “lost” space on Portland’s industrial east side. The site of “Elevated Integration” is located on Portland’s industrial east side along the Willamette River, adjacent to the Eastbank Esplanade, an underutilized, waterfront pedestrian and bike path resurrected as an urban renewal project to counter the discontinuities created by the elevated I-5 highway system. The site previously housed three parking lots that were demolished and recycled to allow for a 103,000 square foot building (24,000 square foot building footprint) and nearly 300,000 square foot urban park. The programmatic elements of the building are designed as a response to the insufficient housing model that currently exists within Portland for homeless families. The vision for “Elevated Integration” was to

create an all-encompassing building that is capable of offering homeless families all vital human necessities under one roof. The integration of these families into an environment designed to promote the ideals of community, wellness, development, and support offers a solution to transition these families into a more stable lifestyle. A supportive approach resides in designing a building capable of self sufficiency and providing basic human necessities. The residents have the ability to gain knowledge and skills that allows them to reintegrate back into society. The project includes a two story public market, three story workforce development sector, public library, residential plinth, and a public park. Integration occurs along two ecologies within the project, environmentally and socially, to ultimately reverse the hindering elements that homeless families encounter and transform those setbacks into opportunities. This reversal is fueled by environmental systems that power the residents’ net-zero community, and by meshing the residents back into a public setting to counter the social isolation that homeless families encounter. The utilization of a completely unique, prefabricated, simply-assembled wall unit that is able to be configured by the residents and local community allows for the empowerment of the residential population. The wall unit is fabricated utilizing local, recycled wooden construction pallets. The illustrated configuration includes thirty-one mixed type units with the ability for this community to fluidly change over time based on the necessities of its residents.

GRAFT ON THE HIGHWAY

DAN KELLY | STEFAN LANGEBEEKE

Located in Louisville, Kentucky, our proposal is located between the 9th street on and off ramps of Interstate-64. Historically, 9th street divides down-town Louisville from West Louisville, which houses the more industrial, sub-urban side of the city. This physical division of the city has also caused a demographic division amongst its citizens; with the predominantly affluent downtown Louisville separated from West Louisville, comprised of a lower income demographic, including 14% of the citizens of Louisville living in poverty. Our site is also located on a very active flood zone along the Ohio River. This has had great implications for the city of Louisville in terms of damage costs, flood prevention costs, and rebuilding efforts. Our proposal seeks to introduce an architectural solution to this flooding issue by elevating the construction above the existing flood wall (55 feet above sea level) and to pre-vent damages caused by future floods. Our elevated proposal also aims to reconnect a divided Louisville through a community plaza above the existing I-64 highway. The proposed 74,500 square foot plaza is nestled between two buildings totaling 87,700 of mixed-use program. 56,000 square feet of mixed demographic residential units (single family units, “community units” consisting of 4 rooms each with a shared common space and bathroom, and one-bedroom “studio” apartments that feature a commercial studio space) and a 31,700 square foot marketplace that houses a grocery store with fresh produce, food stands, local craftsmen merchandise, and art galleries. The marketplace has operable

doors and walls that line the plaza, allowing it to open completely to the outside for events and an outdoor market experience. Weather permitting, these operable walls will allow the entire plaza level to be utilized for community gatherings, art galleries, food markets, and local events or traditions. The orientation of the two buildings and the open area of the plaza allow for plenty of light to flood into the space as those buildings lie on the east and west side of the plaza; the sun path allows for light to flood the space at all points of the day, with the most light pouring in around noon from the south (the sun angle being at 75 degrees at 1:30 on June 21st, and 33 degrees at 1:30 on December 21st). Our elevated plaza allows the natural vegetation below the elevated highways, including new hydrophilic plants that will absorb water, to reclaim the ground plane below and become natural protection from future floods. With the location of our site being right on 9th street (the physical divider between downtown Louisville and West Louisville), our proposal will re-claim portions of the highway’s off and on ramps, increasing the walkability on either side on the highway that leads to a centralized plaza with market spaces on either side. With higher pedestrian activity in this area, that divide will begin to dissipate and a higher concentration of foot traffic crossing 9th street, particularly through our proposal and reclaimed highway ramps, can be expected.

PASSAGE

BRYAN HAZEL | HENRY LEE

The current state of affordable housing that is offered on the Southeast side of Portland is in a dismal state. While investigating the site and surrounding areas we found zero options. In addition, the local extension of the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry plans to expand and create a large campus by 2030 that will bring in multiple research positions and even more jobs that will service the museum. With this in mind our design addresses the lack of housing that is provided in the area, adding safe access to the Eastbank Esplanade, creating a community node for the incoming jobs, addressing pollution that is created by I-5 that is above and adjacent to the site, and creating a cyclical rain harvesting system that uses Portland’s rainy climate to the advantage of the building and its inhabitants. The design creates a new community node that will provide access to amenities that are not currently accessible. The existing site is in the middle of

a food desert and has a desperate need for a local grocery store or venue that could support a farmers market. The 139,000 square foot building is placed on an existing site mainly zoned as industrial, which introduces situations where buildings are occupied from nine to five or not at all. With the design we propose there will be mixed use programming that supports a thriving community at all hours including a library, coffee shop, daycare, gym and shared working space. This will create a safe environment to live and work in regardless of the hour of the day. An environment that is high in crime currently surrounds the site. The objective of the design of the community spaces both indoors and out , is to create a space that provides classes to learn skills that inspire the community and create a safe environment for the workers of OMSI, residents of Passage, and the visitors to the community.

The US Interstate highway system began its trek across the country in the 1950’s under Dwight Eisenhower’s orders, and the land felt its presence im-mediately. Cities saw long established communities split in two, often defined by economic and cultural disparity. One such example is the city of Louisville, Kentucky, where Interstate 64 entered the city in a tangle of lanes that touched down onto 9th Street and divided the city into two halves. The east-ern side of the divide features a thriving downtown filled with museums and nightlife, whereas the west has become a virtual food desert, accommodating government housing and large warehouses. Louisville shares a border with the Ohio River and has a hot climate with a high yearly rainfall averaging 46 inches. The city floods each year with lasting consequences. Currently, an ineffective floodwall running parallel to I-64 wraps its concrete arms around the city, isolating its people from the water’s edge. In fact, the only way to experience the water for both halves is from atop I-64 itself. With 50- and 100- year flood lines reaching far into Louisville, architectural solutions that adapt to flood conditions while repairing the divisions in the city’s fabric are imperative. RECIPROCITY: Mending an Ecosystem through a Floating Community proposes an innovative solution for these complex issues. The proposal reclaims the water’s edge by pulling in the shoreline underneath I-64 and adapting the adjacent floodwall condition to provide water connectivity to the pedestrian. Floating buildings activate a lively public space adjacent to the existing Interstate infrastructure. These structures are designed to adapt to rising flood levels, leveraging their connection to the

existing infrastructure for stability. Central to both sides of the divide, new living and destination spaces, including one- and two-bedroom apartments, public parks, restaurants and water recreation facilities, aim to appeal to all economic strata represent-ed throughout Louisville’s adjacent neighborhoods. The organism at the heart of this floating urban ecosystem is the freshwater mussel. Once a thriving species in the Ohio River, mussels are now subject to many conservation efforts as they have been depleted due to detrimental dredging techniques. Mussels are essential to the river’s ecosystem and this depletion has contributed to the loss of healthy fish and clean water. REC-IPROCITY will leverage mussel farming to create a revitalized, sustainable ecosystem featuring on-site greywater filtration, learning opportunities for the community, farming jobs, restaurant supply and revenue, and a beautified shoreline. A system of ropes beneath the floating structure serves as the new, safe habitat for the mussels. The habitat will be emphasized throughout the site to raise public engagement and awareness about the importance of the ecosystem’s health, now and in the future. just as a mussel grows on its rope, RECIPROCITY features clusters of structures at a variety of scales, providing a human scale to the large project. It is zoned to a final density of 35 one-bedroom and 30 two-bedroom units ac-companied by 3 restaurants and 15 assorted recreational shops and spaces totaling 300,000 square feet.

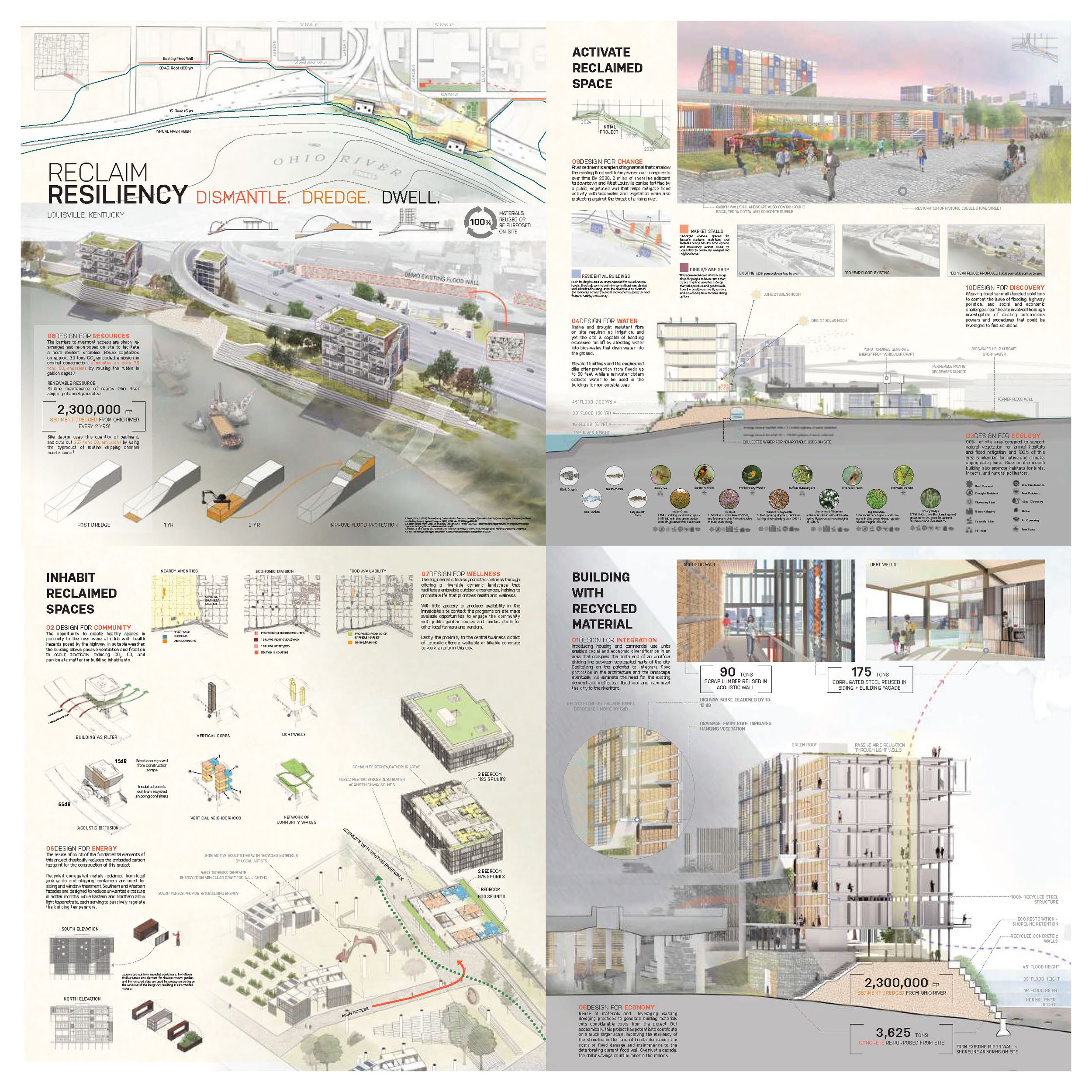

RECLAIM RESILIENCY

RYAN BING | JOE SCHERER

Over time, this proposed process has the ability to restore 2 miles of shore-line access to the inhabitants of Louisville with both public spaces and areas that are optimized for dwelling, while also offering full flood protection from the Ohio River, and improving resiliency of a city which has suffered greatly in the past from devastating floods. By dismantling physical and socioeconomic barriers that have previously prohibited the wellness of area inhabitants, this project rejuvenates riverfront access and creates opportunities for the well-being of residents and nearby res-idents. Using renewable, recycled, and repurposed materials, some of which are byproducts of existing processes, such as dredged sediment from routine shipping channel maintenance of the adjacent Ohio River, this project is able to offer flood protection and reclaim a lost space while also saving over 400 tons of carbon dioxide emissions in just a single phase of completion. In this reclaimed space, people can dwell permanently, safe from environ-mental dangers, including the river itself, and the adjacent highway. By introducing housing and commercial use units in this part of the city, the project promotes social and economic diversification in an area that occupies

the north end of an unofficial dividing line between segregated parts of the city. By integrating flood protection in the architecture and the landscape, the existing decrepit and ineffectual flood wall can be torn down, reconnecting the city with the riverfront, and the concrete wall can be reused in gabion caged retention walls in the new, resilient landscape. This dynamic landscape facilitates enjoyable outdoor experiences, and promotes a life amongst the residents and nearby residents that prioritizes health and wellness. With little grocery or fresh produce availability in the immediate site context, the pro-grams on site make available opportunities to engage the community with public garden spaces and market stalls for other local farmers and vendors. It also offers spaces for a “Swap Shop” to help promote reusing clothing, everyday objects, and ultimately contribute to the notion of extending the life of all materials, in an effort to establish a more circular economy. Finally, the proximity to the central business district of Louisville offers a walkable or bikeable commute to work, a rarity in this city.

REVIVE

GABRIELLE BERNIER | GARRETT SCHAPPELL

Buildings on this site will primarily serve the residents of Louisville, as well as provide housing opportunities to those wishing to live slightly outside the city, while also maintaining easy access to the downtown area. The program of this design is heavily focused on community. In addition to introducing new residential units with varied living options, the ground level will include new community spaces to help revive the west side of I-64. The city of Louisville, KY has a relatively moderate climate. Winter’s average about 47 degrees and summers average about 86 degrees. Because of the site’s location set within a densely populated city, cooling to mitigate the heat island effect in the summer is an important consideration, as well as designing for heat and light below the elevated highway in the winter months. The total square footage of the site is 213,370 sf (about 5 acres), 20 percent of which will be occupied by new buildings (46,900 sf). There is a significant amount of exterior space incorporated throughout the site to encourage maximum outdoor activity, as well as community building. Massing of the buildings respond to the layout

of the city’s preexisting grid that was destroyed upon the construction of the elevated highway. This lay-out aims to recover the grid and create a more inviting space for pedestrians through this city extension. The central exterior “spine” through the site responds to the form of the elevated highway above. Voids were then extracted out for exterior communal gathering spaces for pedestrians traveling through the site. These voids that are created within the building masses provide spaces for pedestrian refuge and community building, as individuals progress through the site between the city and riverfront. This focus on the strategic design of the “in-between” space places more of an emphasis on the journey and less on the destination. These spaces encourage pedestrians to pause for a moment while in route to their destination, without having to go out of their way – promoting time spent outdoors and with other members of the community.

TAKING ROOT

RACHEL BACA | CORA BUTLER

Hovering above the congested knot where I-64 meets the Ohio River, this housing complex takes root in the epicenter of the fracture from Eisenhower’s interstate system. Ripping the city fabric of Louisville, Kentucky, the highway system tore the industrial city from the river that had historically fueled its prosperity, drove its population to the suburbs and prompted the obesity plague of fast food chains along its corridors. An almost entirely renter-occupied neighborhood where half live below the poverty line and a third require food stamps, is desperately in need of a means to escape the cycle of barely scraping by in the city. By boldly nesting above the hotbed, an incessant community is reawakened, a connection to nature is reestablished and a new urban generation of Kentucky farmers is born. With reclaimed highway pedestrian and bike paths leading into the commercial district, the local working class will have a foothold in transforming the 9-5 ghost town into a vibrant model of green living. Property and burglary crimes will be greatly reduced outside of business hours and a vibrant, engaging community will surveil itself through evening and weekend programming including farmer’s markets, harvest festivals and new riverwalk amenities such as kayak and bike rentals, outdoor yoga classes and park visitors. Our rent-to-own business model seeks to increase homeownership from the area’s current 12% and target young millennials. By foregoing the tiresome commutes with local housing, the neighborhood is activated by passionate inhabitants around the clock. Four systems of

gardening harmoniously work together to achieve a healthy living environment in Kentucky’s mild climate. Each of the 144 units comes complete with an array of 4’x4’ square-foot gardening beds that yield surplus creating economic opportunities at the produce market below. Every unit’s glass curtain wall assuages natural light and heat through the use of vine adorned shading screens, while intensive green roofs naturally insulate the units while also supporting the biodiversity of local flora and fauna. Through both active and passive means, polluted highway air below is propelled upwards through a network of air filtering plants before releasing the air above into the sky-high community. Kentucky has the highest rate of fast food restaurants per capita leading to obesity and health issues despite its rich agricultural roots. New businesses will rejuvenate this heritage even in its largest city as clean, local food grown in the complex mitigates its food desert crisis. A restaurant, an organic juice bar, test kitchen spaces and culinary classrooms fill the first four levels of the building off of the North 10th Street entrance. Farm to Table dining is put on full display as each unit not only has a square footage garden to support its occupants twice over, but the lower level 9000+ square foot commercial space bolsters the need for local food sources and creative culinary ventures. Like a tree pushing through a crack in a sidewalk, this housing complex brazenly overtakes the highway to relaunch a community and renew the city’s affinity for nature.