RESOURCES

Designing architecture with the environment cannot be limited to incorporating green or natural elements. More importantly, designing sustainably should mean imagining new kinds of architectural processes entangled with the larger processes that shape the environment as a whole. On a planet exhausted by an unstoppable culture of overconsumption, architecture must be efficient and creative, as these projects, in its use of the available resources. Reusing existing buildings and structures; recycling materials discarded by other industries; inventing circular economies in which the byproduct of certain processes turn into valuable material. Like the use of the materials extracted in the dredging of the bottom of a river, as a material for topographic transformation, or like the recycling of a derelict parking garage as a mat-building where new residential towers can grow.

HIGHER GROUND

ERIC BELL | TATE DELUCCIA

HIGHER GROUND

2020 | VULNERABLE CITIES, VULNERABLE POPULATIONS | Sustainable transitional housing solutions for chronically unsheltered populations in the U.S.

David Franco | Ulrike Heine | George Schafer

Over ninety percent of all homeless LGBTQ+ youth in the ages of 18 to 24 in the city of Santa Cruz are unsheltered. Upon being rejected by their family members, these children and transition-age-youths will resort to sleeping rough under bridges, in cars, or in places that offer little to no security for their well-being. They are at an exponentially higher risk for being the victims of physical abuse, drug abuse, and unsafe sexual practices. Without support, many of these youths will fall into a cycle of criminality that could impact their lives forever. This project will provide a [safe + inclusive] transitional shelter for homeless LGBTQ+ youths in Santa Cruz and will create [engaging + energetic] public spaces for all residents of the city to celebrate a culture of [community + equality]The site is located in an asphalt desert - a section of Santa Cruz’ most valuable real estate dominated largely by surface parking lots. Creating a vibrant public commodity in a dead-zone dominated by the vehicle provides an enriched environment and contributes to the identity of the city as a whole. The proximity of the site to the beach, the boardwalk, and the riverwalk

makes it an attractive destination for residents of the city (the external community) and residents of the project (the internal community).This project creates a gradation of private, semi-private, semi-public, and public spaces that provide the opportunity for the internal and external communities to interact with one another. The residential spaces are raised to the top floor to provide a suite for the LGBTQ+ youth that feels secure yet does not compromise their privacy; giving them an enhanced level of discretion without segregating them from their community and environment. The building is designed for a flood - it is largely built up on piers to ensure that it maintains its facility even in the event of a natural disaster. Santa Cruz’ year-round temperate climate provides the opportunity for high levels of fenestration through the building, opening the facade to operable louvers, cross ventilated public spaces, and shaded out-door gathering places. Using all of these strategies in concert, the Higher Ground Center aims to provide a place where anyone can belong.

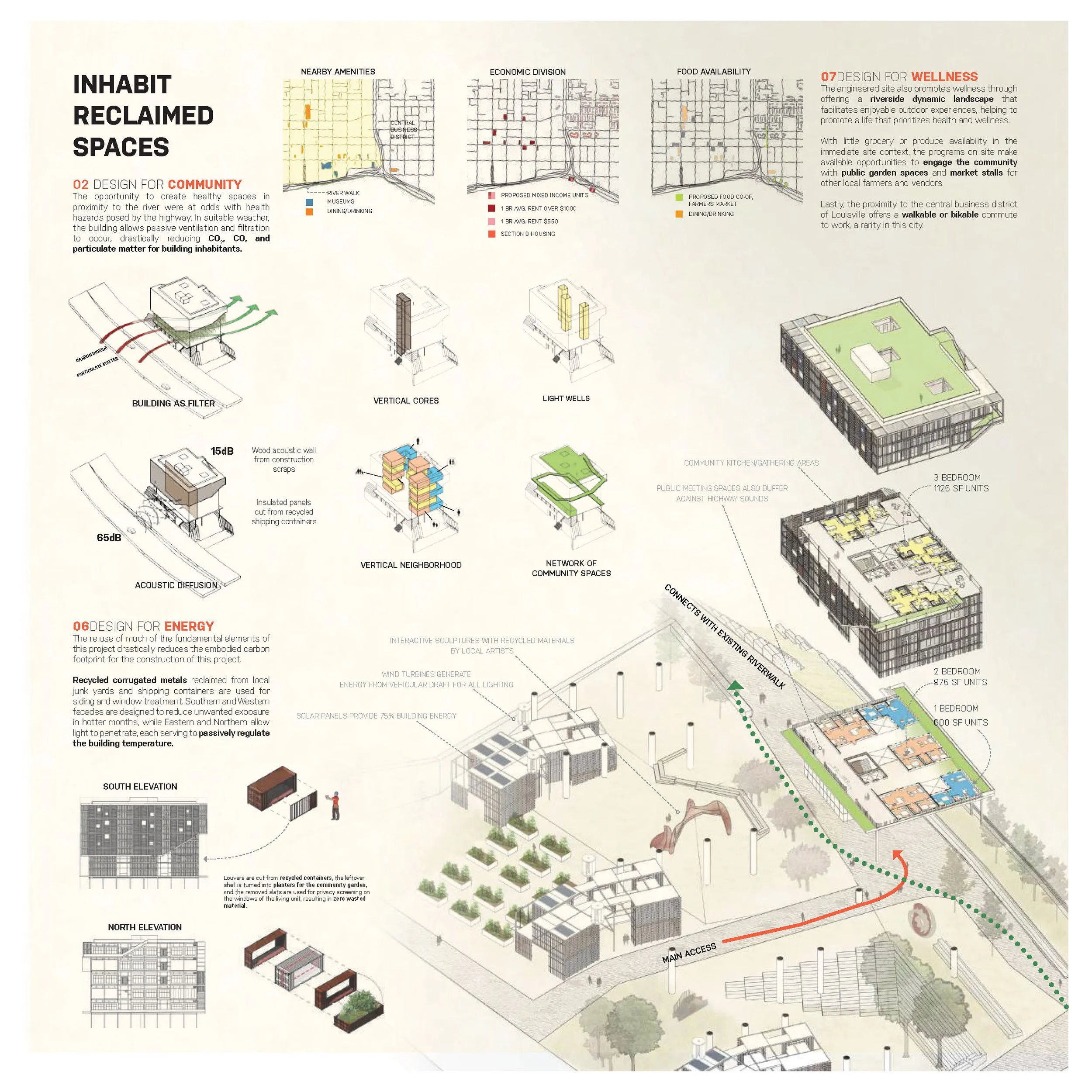

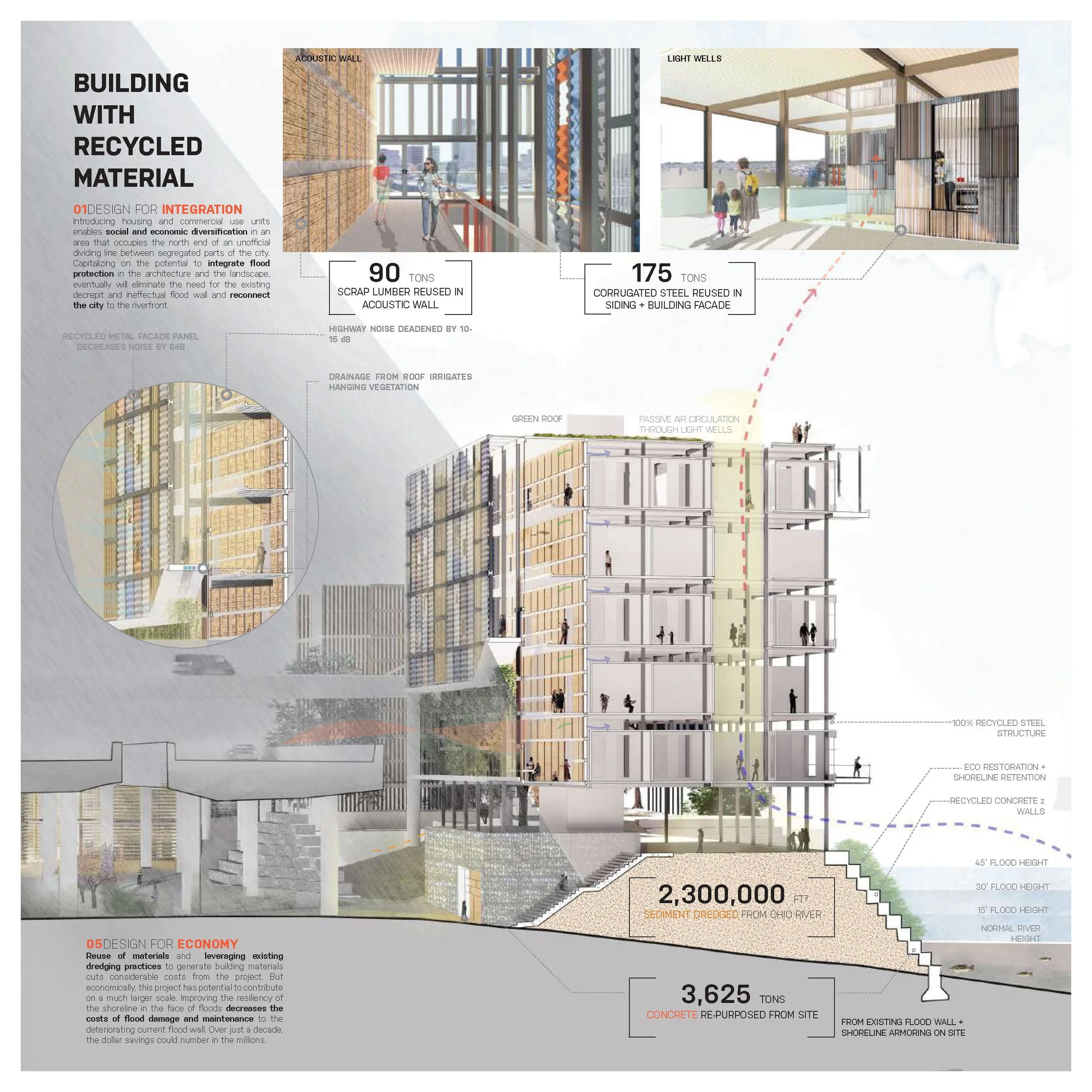

Over time, this proposed process has the ability to restore 2 miles of shore-line access to the inhabitants of Louisville with both public spaces and areas that are optimized for dwelling, while also offering full flood protection from the Ohio River, and improving resiliency of a city which has suffered greatly in the past from devastating floods. By dismantling physical and socioeconomic barriers that have previously prohibited the wellness of area inhabitants, this project rejuvenates riverfront access and creates opportunities for the well-being of residents and nearby res-idents. Using renewable, recycled, and repurposed materials, some of which are byproducts of existing processes, such as dredged sediment from routine shipping channel maintenance of the adjacent Ohio River, this project is able to offer flood protection and reclaim a lost space while also saving over 400 tons of carbon dioxide emissions in just a single phase of completion. In this reclaimed space, people can dwell permanently, safe from environ-mental dangers, including the river itself, and the adjacent highway. By introducing housing and commercial use units in this part of the city, the project promotes social and economic diversification in an area that occupies

the north end of an unofficial dividing line between segregated parts of the city. By integrating flood protection in the architecture and the landscape, the existing decrepit and ineffectual flood wall can be torn down, reconnecting the city with the riverfront, and the concrete wall can be reused in gabion caged retention walls in the new, resilient landscape. This dynamic landscape facilitates enjoyable outdoor experiences, and promotes a life amongst the residents and nearby residents that prioritizes health and wellness. With little grocery or fresh produce availability in the immediate site context, the pro-grams on site make available opportunities to engage the community with public garden spaces and market stalls for other local farmers and vendors. It also offers spaces for a “Swap Shop” to help promote reusing clothing, everyday objects, and ultimately contribute to the notion of extending the life of all materials, in an effort to establish a more circular economy. Finally, the proximity to the central business district of Louisville offers a walkable or bikeable commute to work, a rarity in this city.

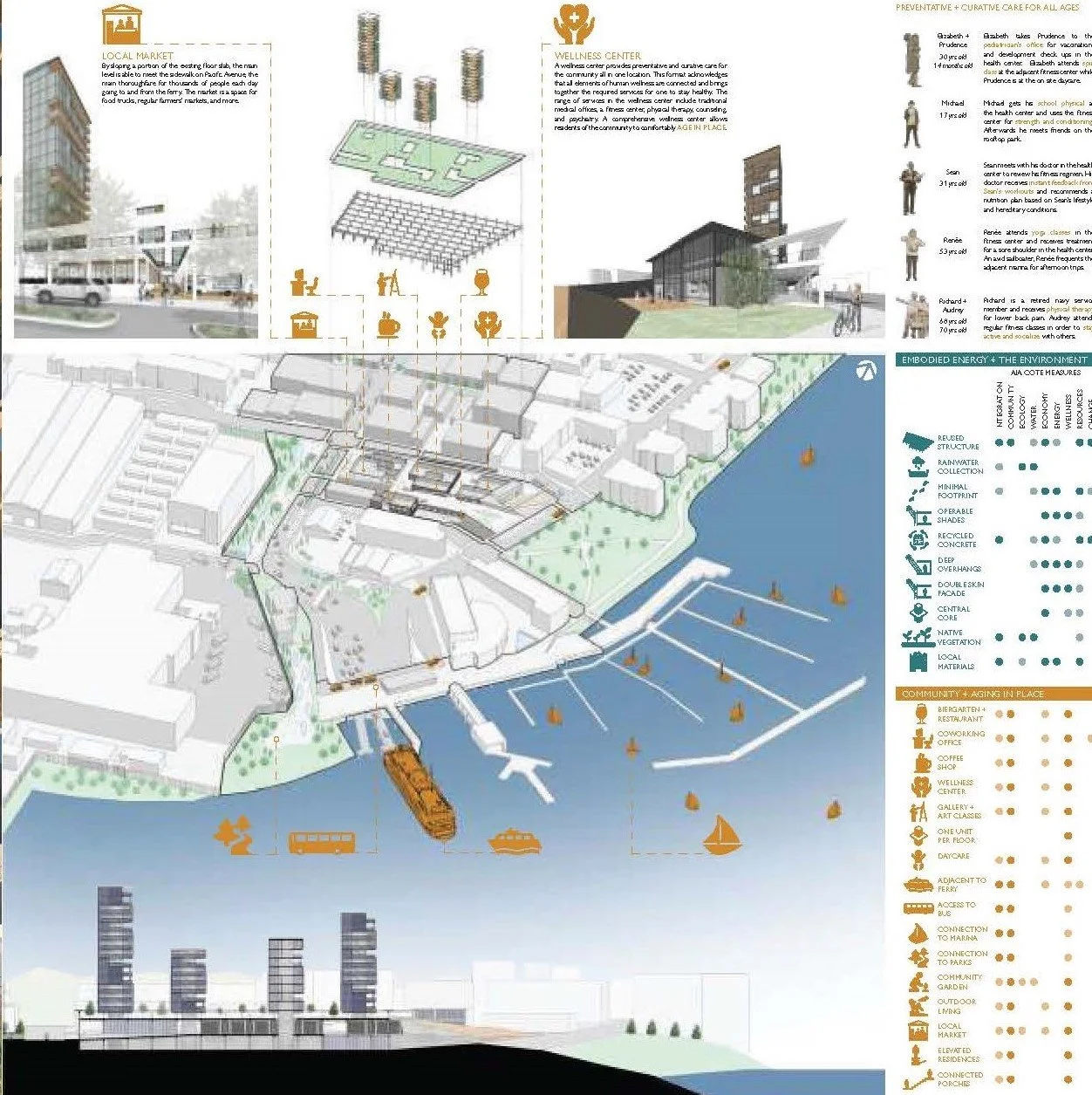

Acclimate is a project about the power of taking urban spaces from cars and giving it back to people. Located in downtown Bremerton, Washington, this project is the adaptive reuse of a three story, 500 spot parking garage. Originally built in the 1960s out of reinforced concrete, the structure’s original purpose was a J.C. Penney department store. In the late 20th century, the structure was converted into a parking garage. With a footprint of 80,000 square feet, the opportunity to positively impact the fabric of downtown is tremendous. The project is designed as two distinct phases. The first phase involves creating public programming within the existing 152,000 square foot building. With a floor, structure, and a roof already in place and an open floor plate, these spaces would be able to be built out with relatively low investment. The second phase involves building four residential towers with a footprint of just 280 square feet each, above the existing structure. Once 48,000 square feet of residential programming is added to the project, the total usable square feet adds up to roughly 200,000 square feet. The project pushes the boundaries of what’s possible while remaining rooted in the economics and schedule constraints of developing close to a quarter of a million square feet. The core concept of the project is the strategic and minimal intervention in an existing structure to create something environmentally

sustainable, economically feasible, socially inclusive, and aesthetically beautiful. The intention behind every move is the maximum impact for minimal investment. The primary strategy of course, is the decision to reuse the existing structure. Given the world’s existing building stock and rapid urbanization of cities all over the world, adaptive reuse as a sustainable strategy is as timely as ever. In this project, reusing the concrete alone will save over 1.1 million pounds of CO2, equivalent to the annual carbon footprint of 114 cars. It will save on the pro-duction of new resources and the intensive amount of energy and resources needed to construct new buildings. Fifty residences are elevated in four different towers to provide views of the surrounding context, connecting people to the city of Bremerton. A small footprint cuts down on demolition and provides the unique opportunity for every resident to have an entire floor plate as their residence. The minimal structure of the towers is accomplished through a reinforced concrete core that houses the towers’ elevator, stairs, utility chase, and a bathroom on each floor. LVL beams are fixed to the core and support the 5-ply CLT floor slabs. A topping slab is provided to minimize acoustic transmission between units. By leveraging the Pacific Northwest’s supply of wood, the project cuts down on embodied energy and uses a renewable resource native to the area.

Along the major artery of Tucson, Arizona, “Historic 4th Avenue”, we see a 2 year turnover rate as well as a significant age dependency ratio. However, not only should an Architecture project address societal issues but also the issue pertaining to climate, and in this case specifically Tucson’s climate. With a low sun angle and dry-heat, Tucson holds two of the most significant thermal comfort issues.

A proposed development to this unique site needs to provide comfortable outdoor spaces for its users to remain socially active, as is a need for the elderly (refer to the age dependency). It must also provide opportunities for its occupants to engage with the ecologies and daylight of Tucson. This will improve the psychological state of its occupants and encourage them to stay in this city for a longer period of time.

By integrating the Architecture with Tucson’s climate through the tapering form, and by introducing site-specific ecologies as well as the implementation of public courtyards, the user’s health and wellness will be improved through the promotion of social interaction in the community. The architectural proposal contains 6 college housing units, 3 single family housing units, a grocery store, a coffee shop, and a book store totaling at 18,500 sq. ft.

HEALING THE GROUND

AMANDA KRISTOFF | ELISA PADILLA

HEALING THE GROUND

2017 | REFUGEES WELCOME | Reinventing the Architectural Possibilities of a Refugee Center in the Heart of Madrid

Ufuk Ersoy | David Franco | Ulrike Heine

Healing [the] Ground is an architectural project in Madrid, Spain in response to the current refugee crisis in the European Union. The project is a radical reuse and adaptation of an existing underground parking that eliminates 481 car spots in the heart of Madrid. Having 66% of the total existing area being reused for passive air-cooling, 84% of the infrastructure recycled, 143% of storm water captured and stored on site, and only 5,900 of new sq ft of built intervention, the project is highly active in the ecosystem of the city. As of today, 1.3 Million refugees -the majority from Middle Eastern countries- have fled their homelands seeking asylum in the EU. In 2015, Spain made a commitment to the relocation of 9,363 refugees but only 1,286 have been officially relocated. Madrid has vocalized an exceptional positive feeling towards welcoming refugees into their community making our site a prime location for our project. Through the architectural intervention proposed driven by adaptive re-use strategies and passive systems, our project’s program focuses on creating a shared space for both refugees and locals to interact and avoid isolation. It encourages the integration of refugees into their new community through the manipulation of the urban landscape and the spatial qualities of the built environment. The site is the Santa Maria Soledad de Torres Acosta Plaza located just North of the major circulation vein, Gran Via. Currently, the existing space holds a vast and underused plaza with three levels of parking below grade. Our proposal is to renovate the plaza creating a healing ground for refugees while simultaneously providing a sustainable design solution through the recycling of

the existing, yet, underused parking structure. The introduction of local flora and fauna and passive systems play a key role in the overall design strategy. Having the majority of the program located below grade, allows us to maintain an open plaza space at ground level while taking advantage of the open space left by the parking structure. Canopies of varying programs symbolize protection and a helping hand for refugees. The Integration Center and the Children’s Center are designed to foster a safe place for refugees that seek help. A Café at ground level, right above a Gallery space promotes the interaction and cultural acceptance between locals and refugees. The landscape design has been meticulously thought out by selecting specific plant species local to the region and native to the refugee countries not only to create a comforting and welcoming environment, but to attracts local fauna such as birds and butterflies into the courtyards. Pre-conditioned air provides thermal comfort in the hot and dry climate while a water retention system supports a natural urban landscape created throughout the plaza. The programmatic elements of the site suit the needs of both refugees and locals providing plenty of opportunity for social interaction. By addressing the wellness of the refugees, the community as a whole begins to thrive. Ultimately the goal of the project is to help provide resources and opportunities to lessen the burden of integration and create a sustainable space resulting in communal wellness.