Each year, the AIA COTE® Top Ten for Students Competition recognizes ten exceptional student design studio projects that integrate health, sustainability, and equity. These projects are assessed according to the same categories used for the AIA COTE Top Ten Award and the AIA Framework for Design Excellence. The COTE Top Ten Awards are known for recognizing excellence in sustainable design.

ABOVE THE MARSH

MIA WALKER | LUCAS SCHINDLAR

GROWING TOGETHER UNDER ONE ROOF

2022 | TOURISM AS AN ENVIRONMENTAL DISASTER | The impacts of tourism on cultures, communities and environments

Ulrike Heine | David Franco | George Schafer

Above The Marsh seeks to solve the disconnect in Sunset Beach, North Carolina, a coastal community that continues to be washed away with rising sea levels and land erosion and a population that is aging and lacking diversity. Our design protects the coast from flooding and erosion with a living shoreline composed of a native marshland ecosystems. In addition, Above The Marsh’s goal is to bring a new tourist that can have an experience through a hostel work exchange along the Intracoastal Waterway that focuses on ecotourism and teaching sustainable traveling habits. With an artificial, but natural protection, the site can provide activities to attract new populations such as agriculture, retail shops, and low impact boating, that would otherwise not be possible on a site bound to be submerged under water within future decades through a series of building, harvesting, and inhabiting from land to sea. Building protection for the community and utilizing local dredged soil and marsh plants to redevelop a marsh ecosystem that has become lost to Sunset Beach. Native species of flora and fauna have become destroyed for housing development and depleted with increased wake activity. The utilization of a living shoreline will bring back these lost ecosystems, and can protect Sunset Beach from complete flooding as sea levels continue to rise. This shoreline will be a complete composition of coastal plants, sediments, and oysters that filter and absorb water, create natural wave barriers, and attract local marine life. Harvesting the site begins following the living shoreline development.

This brings agriculture and aquaculture to the site combining popular economies of inland and coastal North Carolina. These crops are organized based on sunlight and growing properties that rotate through the year, while becoming harvested in offseasons using greenhouses that provide year round produce to the site and Sunset Beach community. Above The Marsh incorporates an aquaculture center to harvest local fish and oyster populations using sustainable methods to avoid overfishing and depleting these ecosystems. Inhabiting the site brings in a population of young travelers that want to give back to the Earth and depleted communities. By providing service jobs on site in various disciplines of agriculture, aquaculture, and restaurant and retail service, travelers can work, while experiencing the North Carolina coast to the fullest. Hostels provide short term stays with immersive views of the developed marsh, while taking advantage of coastal breezes and sunlight to create passive strategies within the units. Above The Marsh creates low impact boating that uses kayaks and paddleboards that create small wakes and low harm on surrounding ecosystems, while completely immersing people within their environments. Each strategy focuses on redeveloping Sunset Beach into a ecotourism hub along the Intracoastal Waterway with protecting and diversifying the depleted community its main goals. Above The Marsh displays how a site can bring populations and activities together that would not be possible until a location is protected as sea levels continue to rise and tourists abuse the places they visit.

THE CRAFT, THE TRADITION AND THE CELEBRATION OF CULTURE

OLIVIA WIDEMAN | ANGELA KRAUS

GROWING TOGETHER UNDER O

NE ROOF

2022 | TOURISM AS AN ENVIRONMENTAL DISASTER | The impacts of tourism on cultures, communities and environments

Ulrike Heine | David Franco | George Schafer

The Craft, the Tradition, the Celebration of Culture, aims to solve the disconnect between culture, place, and estranged descendants through an immersive, hands-on learning center that celebrates the trades and traditions through practice. The area spanning from Jacksonville, FL to Wilmington, NC is known as the Gullah Geechee Heritage Corridor. With the rise in development and tourism along the coast of South Carolina, the ecosystem is on the brink of an environmental disaster. The increase of storms and flooding is detrimental to the environment that was once self-sustained. St. Helena Island is the last South Carolina Sea Island along the corridor where the Gullah still lives and practices. The sea islands and culture are at risk of vanishing completely if traditions are not practiced and passed down to younger generations. Self-identity strengthens character and confidence. When children have a deeply rooted understanding of their heritage, their self-worth is increased. Studies show the most impactful age range for character development is between the 2nd and 8th grades. Trades and traditions from locals are passed onto students attending the 7-day heritage program, in hopes to strengthen cultural identity and self-importance. Situated across from the site is the Penn Center. This historical campus became one of the first schools in the country to provide a formal education to previously enslaved West Africans. Today the center serves as a museum, community center, and historical landmark.

Agriculture, cuisine, build + restore, art + folklore are the four programmatic approaches, each of high value to the culture and resilience to the direct community and environment on St. Helena Island. Re-introducing Carolina gold and a vegetable garden allows for year-round interest to inspire education. Students learn about the process’ of soil preparation, sewing seeds, maintaining, and harvesting crops. Once harvested students create Gullah dishes with the three traditional methods of cooking: grilling, stewing, and wood burning. Other methods of cuisine include preparation and preservation, from deshelling and creating spices, to canning and salt-curing. Outreach donates excess crops and meals to local markets for profit. Students learn traditional construction methods and blacksmithing in the tool shop. In the material shop students learn processes of harvesting, carpentry, and joinery, as well as creation of the vernacular material. Outreach consists of repairing and building structures on the island. Students experience folklore and language through immersive guided tours along the site. Students learn traditional song, dance, and instruments during their stay. Outreaches include festivals where students can sell and celebrate their crafts. Lofts are playfully incorporated in each zone to spark a sense of discovery and immersion. Each zone incorporates unfolding furniture elements that support the learning experiences, as well as indoor-outdoor classroom spaces that fully immerse the student in place.

RESTORING A HAVEN

WILLIAM SCOTT | CONNOR SMITH

GROWING TOGETHER UNDER ONE ROOF

2022 | TOURISM AS AN ENVIRONMENTAL DISASTER | The impacts of tourism on cultures, communities and environments

Ulrike Heine | David Franco | George Schafer

Starting in the mid-20th century, artists and creatives in the New York City queer community adopted Fire Island Pines as a haven and destination. The affordability and opportunity to create their own community underpinned an environment that cultivated free expression. But over the years, like many other creative enclaves in New York and elsewhere, higher income brackets have infiltrated in search of valuable property and cachet. This has priced out creatives and ultimately jeopardized The Pines’ identity and sense of community, reframing the place as merely a party destination. Popularity and limited housing options exacerbate an inflated rental market, with summer 4-bedroom 4-week rate averages exceeding $19,000. Most visitors to The Pines are white gay men who own a home, know someone who owns a home, or can afford to rent for the season. This has resulted in an insular community that runs against current and past movements in the queer discourse, resulting in a less inclusive destination. Additionally, The Pines suffered severe damages following Hurricane Sandy, with flooding impacting most structures. It continues to face existential threats as a barrier island, with significant public resources directed toward dune restoration and breach prevention. The design increases 12-month unit occupancy, benefitting the community economically and culturally in the off season through creative residencies. In peak season, the program changes to tourist-centered housing - connecting visitors with work of the creatives. Changing programs are enabled by a glulam timber structural system which facilitates adaptability from daily user changes to long-term relocation. To improve housing affordability, the design introduces greater density. Slightly taller structures, without compromising neighboring single-family homes, along with adaptive interior partitions allow for higher occupancy in peak months and space for creatives the remaining 9 months.

The Pines is notably inaccessible for the physically handicapped due to its elevated boardwalk system. To address this, every programmatic element has direct access via ADA compliant circulation and has multiple flat connections to the public boardwalk. Due to the stereotypically white, muscled party culture of The Pines, some members of the LGBTQ+ community may still feel that it is not the place for them. So, the design gives agency and privacy to visitors of all backgrounds. Agency over spatial tectonics through movable interior partitions. Agency over social interaction through operable louver systems on public frontages. And privacy by lifting all entrances 12 feet above boardwalk level. The interior courtyard provides an open, social environment for visitors without needing to engage in the scene. Part of the queer influence on Fire Island has been the adaptation of heteronormative single family homes into queer spaces – this attempts to enable a greater level of adaptability from day one. The Army Corps of Engineers has deployed millions of dollars to elevate the nearly 4,500 at-risk structures on Fire Island, which amount to nearly $1.4 billion in property value. The design addresses the growing flooding threat by elevating all first levels and mechanical systems above the NOAA’s 6ft maximum projected flood level. Additionally, all boardwalk circulation can float on guideposts attached to the building structures. The design also reintroduces native trees and plants to the brownfield site, their roots grounding the sandy soil. Long-term, the structural system, informed by the Open Building movement, can be disassembled and relocated. The well-documented longevity of glulam and minimized member sizes enables much of the system to be packed and moved inland. Overall, the design aims to learn from and reinterpret existing social, environmental, and building strategies to introduce a new approach to building community in Fire Island Pines.

THE CONNECTED FARM

GAUGE BETHEA | JESSE BLEVINS

GROWING TOGETHER UNDER ONE ROOF

2021 | EXPERIMENTS IN COMMUNAL LIVING | Resourcefulness, self-sufficiency and cooperation in the fallout of COVID

David Franco | Ulrike Heine | Andreea Mihalache | George Schafer

The Connected Farm is an intergenerational communal housing project which impacts its residents by implementing self-sustainability through agriculture and the efficient utilization of resources. The Connected Farm is situated 15 miles off the coast of Maine on the island of Vinalhaven which is largely undeveloped and has a vast range of ecological diversity. The project site sits on 5-acres which acts as a connection point between this undeveloped land and the dense downtown district. This area is categorized by a humid climate with cold winters and heavy snowfall. It has temperatures ranging from 19 to 71 degrees. Some of the largest economies on the island are farming and fishing which brings the community together during their productive seasons. The Connected Farm aims to address the opportunities present on the island such as shortage of sustainable housing, seasonal job instability, and insufficient resources such as internet access which leads to island flight for young individuals and generational disconnect for those aging in place. The solution is to create a community that is 100% self-sufficient to reduce housing costs, supply year-round income opportunities through agriculture and technology-based jobs, and provide a one stop-shop that promotes connection among all generations. The farm connects to the existing grid which creates blocks on the site that are allocated based on the connection to the surrounding area and how production or people would circulate around the site. The buildings are placed on a grid designed for integration to facilitate socialization and agricultural production. 75% of the site is dedicated to agriculture which allows for 41,000 pounds

of total food production and generates a 300% annual surplus. Each component within the agricultural system has a purpose and is designed to create a holistic cycle. The farm creates a thriving community that promotes human connection among all generations by providing access to social spaces, technology, and a live-work environment. Throughout the site, there are multiple means of income opportunities through technology and agriculture which provides year-round food production and incentives to stay on the island. The inspiration for this project came from the regional New England Connected Farmhouse. It was originally designed for agrarian reform and allowed New Englanders to have home-based industries while continuing to work on a centralized farm. With this concept, we designed a site which encourages a work, home, and play environment. The buildings are designed to be all-encompassing and are capable of producing income along with providing the comfort of home. The site accommodates housing for 96 residents with 24 ADA accessible rooms. Each building utilizes sustainable strategies to reduce energy consumption and water demand. Local materials are also used for affordability and reduction of the overall carbon footprint. This site integrates agriculture and technology to foster a sustainable future for the residents of Vinalhaven. The Connected Farm plays a vital role in providing an end to social isolation and building a sense of community by bringing generations together and providing social and economic opportunities through the power of food.

GROWING TOGETHER UNDER ONE ROOF

THALY JIMENEZ | DANIEL MECCA

GROWING TOGETHER UNDER ONE ROOF

2020 – VULNERABLE CITIES, VULNERABLE POPULATIONS | Sustainable transitional housing solutions for chronically unsheltered populations in the U.S.

David Franco | Ulrike Heine | George Schafer

Growing Together Under One Roof is a transitional housing project located in Fairbanks, Alaska. The 165,309 square feet facility houses domestic violence survivors who may not have the resources needed to escape their difficult home lives. The housing complex consists of nineteen single home units and eighteen family units which were placed strategically throughout the building. The housing units are divided into private units and less private units. The private units are placed towards the back of the building where the river serves as a natural barrier to avoid public entrance. The less prive units are hidden in plain sight at the front of the building where the residents have a chance at interacting with the public. This will suit residents at different stages of the recovery process by helping them integrate slowly into the community. Additionally, programming for the local community such as a community garden, playground, library, computer lab, and vertical farming seeks to bring the nearby community together by providing neighbors of all ages with a place where they can come together and continue activities such

as cultivating crops during Fairbank’s long winter months. Due to Alaska’s geographical location, the citizens of Fairbanks find themselves facing extreme weather conditions every year which can significantly affect their daily lives, the environment around them, and their physical and mental health. The three main environmental fac-tors that played a role in the design of our project were natural light exposure, permafrost and long, freezing winter months. Extensive light exposure during summer months and low light expo-sure during winter months guided us in the placement of our units which are located along the south facade of the building. Addition-ally, artificial lighting was added as a source of lighting during winter months. ETFE bubbles on the envelope can be deflated to reduce sunlight during long summer months and provide insulation during winter. A high level of sustainability was achieved by utilizing several renewable energy sources as a strategy.

RECLAIM RESILIENCY

RYAN BING | JOE SCHERER

RECLAIM RESILIENCY

2019 | LOST SPACES | Architectural solutions for leftover space created by America’s elevated urban highways

David Franco | Ulrike Heine | George Schafer

Over time, this proposed process has the ability to restore 2 miles of shore-line access to the inhabitants of Louisville with both public spaces and areas that are optimized for dwelling, while also offering full flood protection from the Ohio River, and improving resiliency of a city which has suffered greatly in the past from devastating floods. By dismantling physical and socioeconomic barriers that have previously prohibited the wellness of area inhabitants, this project rejuvenates riverfront access and creates opportunities for the well-being of residents and nearby res-idents. Using renewable, recycled, and repurposed materials, some of which are byproducts of existing processes, such as dredged sediment from routine shipping channel maintenance of the adjacent Ohio River, this project is able to offer flood protection and reclaim a lost space while also saving over 400 tons of carbon dioxide emissions in just a single phase of completion. In this reclaimed space, people can dwell permanently, safe from environ-mental dangers, including the river itself, and the adjacent highway. By introducing housing and commercial use units in this part of the city, the project promotes social and economic diversification in an area that occupies

the north end of an unofficial dividing line between segregated parts of the city. By integrating flood protection in the architecture and the landscape, the existing decrepit and ineffectual flood wall can be torn down, reconnecting the city with the riverfront, and the concrete wall can be reused in gabion caged retention walls in the new, resilient landscape. This dynamic landscape facilitates enjoyable outdoor experiences, and promotes a life amongst the residents and nearby residents that prioritizes health and wellness. With little grocery or fresh produce availability in the immediate site context, the pro-grams on site make available opportunities to engage the community with public garden spaces and market stalls for other local farmers and vendors. It also offers spaces for a “Swap Shop” to help promote reusing clothing, everyday objects, and ultimately contribute to the notion of extending the life of all materials, in an effort to establish a more circular economy. Finally, the proximity to the central business district of Louisville offers a walkable or bikeable commute to work, a rarity in this city.

ELEVATED INTEGRATION

GEORGE SORBARA | HUNTER HARWELL

GROWING TOGETHER UNDER

2019 | LOST SPACES | Architectural solutions for leftover space created by America’s elevated urban highways

David Franco | Ulrike Heine | George Schafer

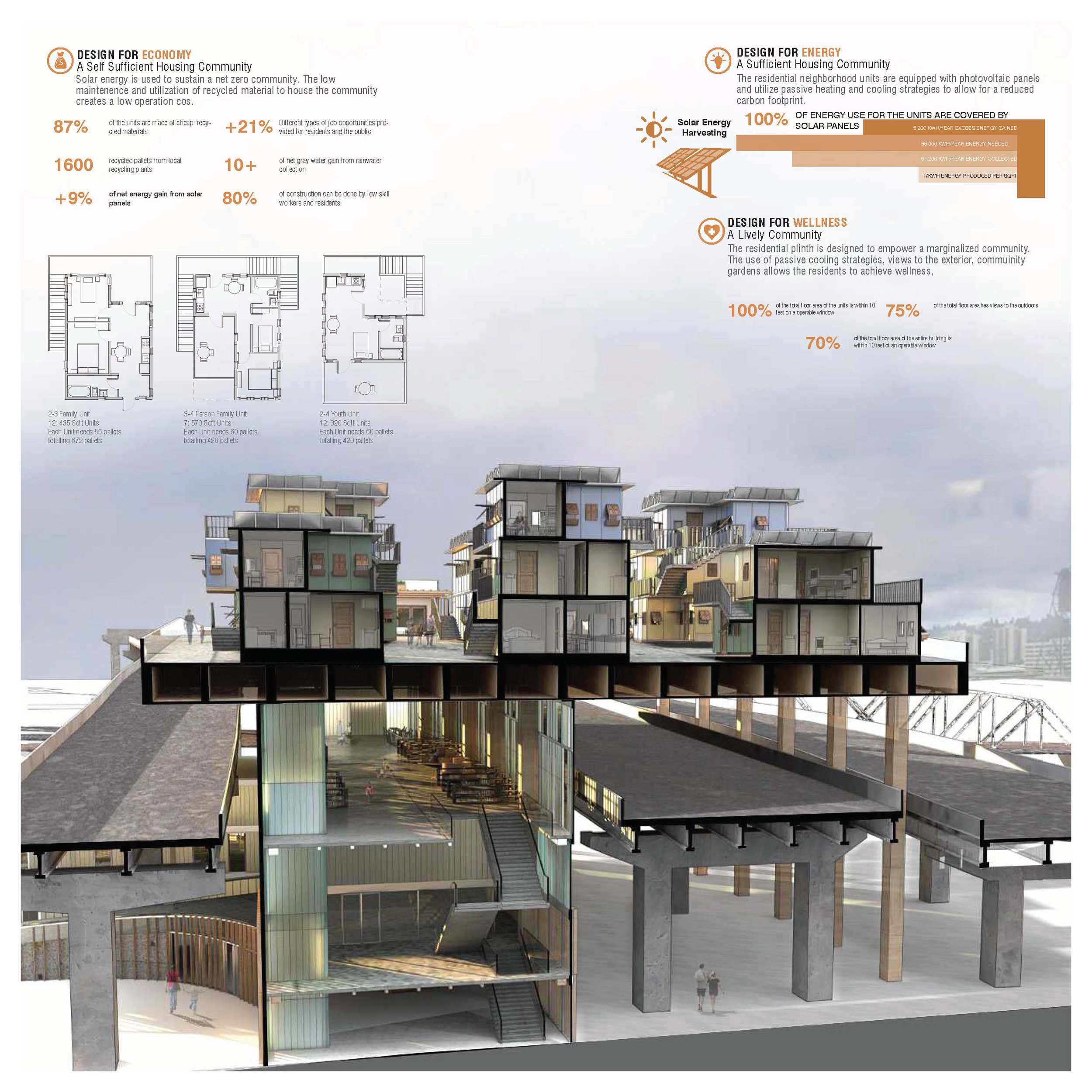

“Elevated Integration” is a direct response to Portland, Oregon’s growing number of families facing homelessness. As of 2019, there were 4,015 individuals facing chronic homelessness within Portland. Seventeen percent of those individuals, including 374 children, belong to a family that is facing chronic homelessness. The necessity for a response to this situation is imperative and the very essence of “Elevated Integration” at its purest form. “Elevated Integration” is also an architectural response regarding the leftover spaces that are a byproduct of elevated urban highways. From uninhabitable zones to discontinuities in the urban and social fabric of cities, the interstate highway system has had seemingly irreversible consequences for America’s urban ecologies. “Elevated Integration” is a design solution to support a marginalized population of homeless families while simultaneously mending a discontinuity within a “lost” space on Portland’s industrial east side. The site of “Elevated Integration” is located on Portland’s industrial east side along the Willamette River, adjacent to the Eastbank Esplanade, an underutilized, waterfront pedestrian and bike path resurrected as an urban renewal project to counter the discontinuities created by the elevated I-5 highway system. The site previously housed three parking lots that were demolished and recycled to allow for a 103,000 square foot building (24,000 square foot building footprint) and nearly 300,000 square foot urban park. The programmatic elements of the building are designed as a response to the insufficient housing model that currently exists within Portland for homeless families. The vision for “Elevated Integration” was to

create an all-encompassing building that is capable of offering homeless families all vital human necessities under one roof. The integration of these families into an environment designed to promote the ideals of community, wellness, development, and support offers a solution to transition these families into a more stable lifestyle. A supportive approach resides in designing a building capable of self sufficiency and providing basic human necessities. The residents have the ability to gain knowledge and skills that allows them to reintegrate back into society. The project includes a two story public market, three story workforce development sector, public library, residential plinth, and a public park. Integration occurs along two ecologies within the project, environmentally and socially, to ultimately reverse the hindering elements that homeless families encounter and transform those setbacks into opportunities. This reversal is fueled by environmental systems that power the residents’ net-zero community, and by meshing the residents back into a public setting to counter the social isolation that homeless families encounter. The utilization of a completely unique, prefabricated, simply-assembled wall unit that is able to be configured by the residents and local community allows for the empowerment of the residential population. The wall unit is fabricated utilizing local, recycled wooden construction pallets. The illustrated configuration includes thirty-one mixed type units with the ability for this community to fluidly change over time based on the necessities of its residents.

ACCLIMATE

CAMERON FOSTER | PHILIPP RIAZZI

ACCLIMATE

2018 | AGING IN THE CITY | Architectural strategies to create multigenerational urban communities

Dan Harding | Ulrike Heine | David Franco

Acclimate is a project about the power of taking urban spaces from cars and giving it back to people. Located in downtown Bremerton, Washington, this project is the adaptive reuse of a three story, 500 spot parking garage. Originally built in the 1960s out of reinforced concrete, the structure’s original purpose was a J.C. Penney department store. In the late 20th century, the structure was converted into a parking garage. With a footprint of 80,000 square feet, the opportunity to positively impact the fabric of downtown is tremendous. The project is designed as two distinct phases. The first phase involves creating public programming within the existing 152,000 square foot building. With a floor, structure, and a roof already in place and an open floor plate, these spaces would be able to be built out with relatively low investment. The second phase involves building four residential towers with a footprint of just 280 square feet each, above the existing structure. Once 48,000 square feet of residential programming is added to the project, the total usable square feet adds up to roughly 200,000 square feet. The project pushes the boundaries of what’s possible while remaining rooted in the economics and schedule constraints of developing close to a quarter of a million square feet. The core concept of the project is the strategic and minimal intervention in an existing structure to create something environmentally

sustainable, eco-nomically feasible, socially inclusive, and aesthetically beautiful. The intention behind every move is the maximum impact for minimal investment. The primary strategy of course, is the decision to reuse the existing structure. Given the world’s existing building stock and rapid urbanization of cities all over the world, adaptive reuse as a sustainable strategy is as timely as ever. In this project, reusing the concrete alone will save over 1.1 million pounds of CO2, equivalent to the annual carbon footprint of 114 cars. It will save on the pro-duction of new resources and the intensive amount of energy and resources needed to construct new buildings. Fifty residences are elevated in four different towers to provide views of the surrounding context, connecting people to the city of Bremerton. A small footprint cuts down on demolition and provides the unique opportunity for every resident to have an entire floor plate as their residence. The minimal structure of the towers is accomplished through a reinforced concrete core that houses the towers’ elevator, stairs, utility chase, and a bathroom on each floor. LVL beams are fixed to the core and support the 5-ply CLT floor slabs. A topping slab is provided to minimize acoustic transmission between units. By leveraging the Pacific Northwest’s supply of wood, the project cuts down on embodied energy and uses a renewable resource native to the area.

TRANSFUSION

MICHAEL HORAN | COLE ROBINSON

ACCLIMATE

2018 | AGING IN THE CITY | Architectural strategies to create multigenerational urban communities

Dan Harding | Ulrike Heine | David Franco

Along the major artery of Tucson, Arizona, “Historic 4th Avenue”, we see a 2 year turnover rate as well as a significant age dependency ratio. However, not only should an Architecture project address societal issues but also the issue pertaining to climate, and in this case specifically Tucson’s climate. With a low sun angle and dry-heat, Tucson holds two of the most significant thermal comfort issues.

A proposed development to this unique site needs to provide comfortable outdoor spaces for its users to remain socially active, as is a need for the elderly (refer to the age dependency). It must also provide opportunities for its occupants to engage with the ecologies and daylight of Tucson. This will improve the psychological state of its occupants and encourage them to stay in this city for a longer period of time.

By integrating the Architecture with Tucson’s climate through the tapering form, and by introducing site-specific ecologies as well as the implementation of public courtyards, the user’s health and wellness will be improved through the promotion of social interaction in the community. The architectural proposal contains 6 college housing units, 3 single family housing units, a grocery store, a coffee shop, and a book store totaling at 18,500 sq. ft.

INTERCONNECT

MADISON POLK | HARRISON POLK

ACCLIMATE

2017 | REFUGEES WELCOME | Reinventing the Architectural Possibilities of a Refugee Center in the Heart of Madrid

Ufuk Ersoy | David Franco | Ulrike Heine

Interconnect is a refugee integration center located in Plaza de las Descalzas, designed to aid the process of integration for a growing refugee population in the city of Madrid, Spain. The building occupies the site of an abandoned bank building and shares public plaza space with a historic convent, gallery/event space, contemporary shopping center, and a collection of other mixed-use programs. Interconnect is a contemporary project that responds to its immediate urban context to provide connectivity to an existing network of pedestrian paths in the city center, echoing the belief that refugees should feel like they can belong in Madrid. Currently, Plaza de las Descalzas is an under-activated site in the middle of the pedestrian network that connects a total of 8 streets and 5 public plazas. The footprint of the integration center aims to achieve a strong urban fit by extending a pedestrian path through the site and framing additional public space that will encourage healthy physical and social interactions between local and refugee user groups. The 55,360 square foot integration center provides the city with much needed space for program necessary to help acclimate refugees to a new society; these include a refugee service center, a community media center, and a gallery. The refugee service center provides legal, professional, financial, and childcare services to the refugee population. The community media

center brings locals and refugees together in one space by providing access to information and technology; a coffee bar and café provide flexible space where users are invited to spend their time. Dedicated to culture and art exhibitions, the gallery space is designed to provide physical connection for the building programs, as well as social connection for people by educating them about the refugee experience, and providing space where Madrid and refugee cultures can come together. Practicality and cost efficiency characterize the relationships designed between structure, material assemblies, and sustainable strategies for the project. A series of terraces and large window openings are carved out of the building’s monumental form to provide views of the city, further connecting users to the surrounding urban context. While solid, rough textured Berroquena granite distinguishes the building’s exterior; the interior spaces are open and flexible, defined by indirect natural daylight and grand circulation around a central atrium. Locally sourced materials benefit the control of daylight and thermal comfort in Madrid’s hot, arid climate. Even in its smallest details, the integration center is designed to communicate connectivity to the city of Madrid: it is space designed to help refugees connect to their new home.

LANDSCAPE IN MOTION

CHRIS SANDKHULER | ELIZABETH WIDASKI | JIMMY WOODS

GROWING TOGETHER UNDER

2016 | TECHNIFIED ECOSYSTEMS | The city as an artificial landscape

Ufuk Ersoy | David Franco | Ulrike Heine | Henrique Houayek

Landscape in Motion is a design project to revitalize public green spaces, establish cohesive transportation networks, and optimize urban functions. A civic center offers the city a much needed gathering space for conferences and exhibitions and a bus terminal acts as a transportation hub for the region while offering free bus services. This allows people of all socioeconomic backgrounds and lifestyles to access the downtown and their various workplaces in the region. The redesigned city block extends a designed green space from the city park’s waterfall through the center of the site, terminating it at the site’s northwest corner. This creates

an opportunity to educate the public on the landscape of the area and how to bring sustainability into their lives. The project also inspires activity, offering a myriad of pedestrian paths, biking routes, and a connection to the trails of the park. Landscape in Motion is about finding inspiration in the natural movement of our surroundings from nature to city. Ultimately, the goal is to encourage people to live healthier, more sustainable lives helping both themselves and the community.